007 After Fleming: Colonel Sun

After Ian Fleming's death, Kingsley Amis is recruited to the cause

When Ian Fleming passed away in August of 1964 after suffering a heart attack, his reported final words—said to the crew of the ambulance that was rushing him to the hospital—were “I am sorry to trouble you chaps. I don’t know how you get along so fast with the traffic on the roads these days.” His untimely passing left in doubt the future of his most enduring creation: James Bond. While the movies had taken on a life of their own, the novels were still very much of Ian Fleming, and without him, it didn’t seem like there was any way they would continue. His final book, The Man with the Golden Gun, was published posthumously and against Fleming’s desire. He had just finished the first draft before his death, and he felt the entire thing was rather a mess and wanted to redo it. His publisher, perhaps feeling that any Bond was bankable Bond, insisted that the book was perfectly fine.

It wasn’t. The Man with the Golden Gun was a weak follow-up to what had been an epic previous two books, starting with the marriage of James Bond and the murder of his wife at the hands of Blofeld in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and continuing with an unhinged Bond out for revenge in You Only Live Twice. The finale of that book sees a destroyed, amnesic Bond picked up by Soviet agents who, recognizing the opportunity before them, take Bond back to the Soviet Union, and convince him that he is Russia’s top secret agent. That thrilling cliffhanger opened the door for Fleming to continue in the spirit of those two books, which were emotionally involved and exciting. Unfortunately, that entire premise is dealt with and discarded within the first few pages of The Man with the Golden Gun, and what follows is a thin, unengaging study in padding and half-baked ideas that, as Fleming had said, needed more work.

Unfortunately, his opinion became moot when he passed away, and even though the book was given to another author for a rewrite, in the end, few of that author’s suggestions were taken. The Man with the Golden Gun was published as-is, and everyone who read it probably felt bad to have so many negative things to say about Ian Fleming’s final novel. After its publication, two more short stories were published: “Octopussy” and “The Living Daylights.” “The Living Daylights” is a simple but enjoyable Bond short story, and while “Octopussy” pulls a “Quantum of Solace” and has Bond stand around while someone else tells a story, at least the story is a good one and involves mountain climbing and lost Nazi loot. With the last of Fleming’s contributions in print, and this being before the era of “completed based on the notes of” follow-ups, publisher Glidrose Productions started wondering what to do. If they didn’t get a new Bond product out soon, they would lose the rights to the character. At the same time, the polite but disappointed reaction to The Man with the Golden Gun meant that they couldn’t really just slap something together. Not only would it be disrespectful to the memory of Ian Fleming; but it would also, very likely, sink their greatest cash cow.

After a bit of consideration, it was settled that a new James Bond book would be written. Initially, the idea was to go the route of a stable of writers, each one contracted to write a different novel. But that didn’t pan out, since only one author agreed to subject himself to such scrutiny as would inevitably befall anyone writing a new James Bond book. The author would be the very man to whom they’d given—then ignored the advice of—The Man with the Golden Gun. Kingsley Amis is an author of no small renown. It is practically a given that one won’t get out of any university-level English literature course without reading Amis’ first novel, Lucky Jim. Known primarily for satire, often aimed at upper-class British academic and intellectual culture, he seems a curious pick to carry on the work of Ian Fleming, a writer whose popularity was indisputable but whose quality of writing was up for debate. But to know Amis only as a sly British satirist is to have an incomplete picture of the man.

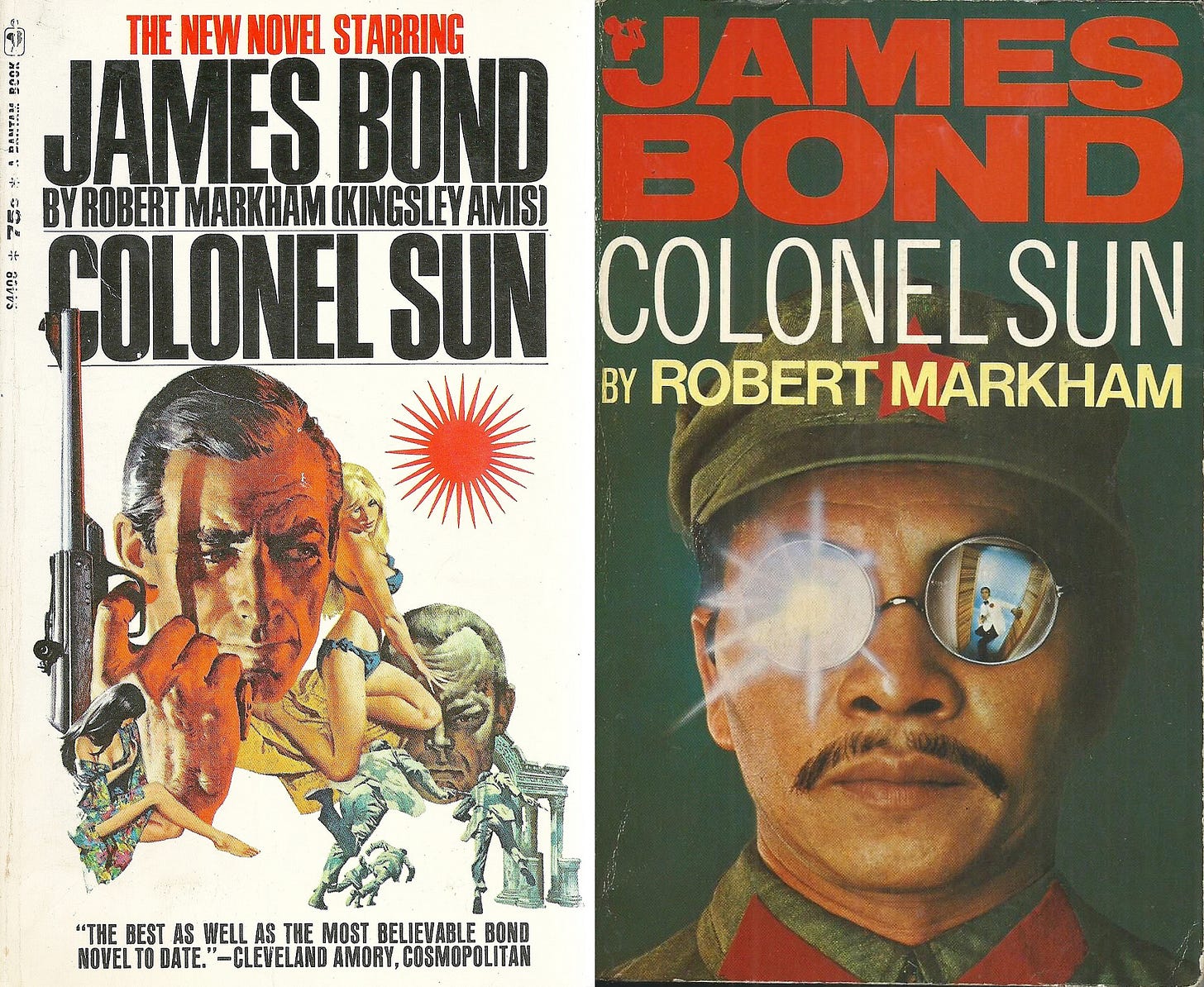

Amis frequently dabbled in other genres, including science fiction, and his love of James Bond was so great that he’d already written two books about the character. The first, The James Bond Dossier, was an exploration of the books from the viewpoint of a literary studies critic. The second, The Book of Bond or, Every Man His Own 007, Amis wrote under the in-joke pseudonym Lt.-Col. William (“Bill”) Tanner (a character from the Bond novels). It is a joke “manual” to becoming a James Bond-esque international man of mystery, relying on quotes, locations, and brand names from the book. Although something of a lark, it actually ends up being a pretty good guide to such things in the Bond novels. It must have been daunting to assume the mantle of the keeper of the James Bond novels, something Amis did under the pen name Robert Markham—somewhat pointlessly. Everyone knew he was the author, and his name often appeared on the covers alongside the Robert Markham pseudonym.

Colonel Sun‘s story begins not long after the conclusion of The Man with the Golden Gun (Bond thinks to himself about the wound left by Scaramanga’s bullet; a later reference is made to the events of You Only Live Twice as well), with Bond and his friend Bill Tanner playing a round of golf while Bond worries that he has settled into an easy life of routine that has dulled his edge. This doesn’t last long, of course. Bond calls on M at home, where the old man is convalescing after a prolonged illness. However, when Bond arrives, M is gone, his two elderly house servants have been executed, and a group of no-nonsense gunmen are waiting to take Bond prisoner. The wily agent manages to foil their plot and escape, but he’s still left with a house full of corpses, a kidnapped head of the British secret service, and a single obviously planted clue pointing him toward Athens, Greece.

In Greece, Bond meets a woman, Ariadne, who is working with the Athens branch of the Soviet Red Army’s GRU (the military’s counterpart/rival to the KGB), and they discover that this isn’t a case of “us versus them.” Or rather, it is, but everyone forgot there might be more than one “them.” In a reflection of the cautious thawing of relations between the West (specifically, Great Britain and the United States) and the Soviet Union, as well as the rising power of China (a frequent thorn in the side of the USSR), Bond discovers that it was the Chinese, not the Russians, behind M’s kidnapping.

And an attempted kidnapping of Bond in Athens was interrupted by the Russians, who wanted to kidnap Bond for the totally unrelated reason of, “James Bond just showed up in Athens, so something crazy is probably about to happen; let’s find out what.” Bond agrees to team up with the local Soviets in a joint effort to uncover and foil whatever plan it is the Chinese, led by sadistic People’s Liberation Army colonel Sun Liang-tan, are hatching. Sun’s gunmen put a premature end to the collaboration when they kill the local Soviet bureau chief, leaving just Bond, Ariadne, and a tough old Greek partisan named Niko Litsas to save M, track down Sun, and spoil the Chinese plot to frame England for the murder of a bunch of world leaders at a secret meeting with the Soviets on a remote Greek isle.

Colonel Sun is a close approximation to Fleming’s style. At the same time, there’s a richer weaving of the story than was customary in Fleming’s writing, which could at times have a youthful energy about them that resulted in some slapdash writing, so anxious to get to the action was Fleming. But there is also the undeniable hint of Amis the satirist lurking just beneath the surface. Sometimes it’s a good-natured ribbing of Ian Fleming’s books, as when Amis prominently mentions the warm, dry handshake of a couple of people whom Bond befriends (mentioning this would later become de rigueur in Bond novels, only without the self-awareness Amis brings to it). Other times, Amis is poking fun at the Bond movies, as when Bond reflects on the uselessness in the end of all the gadgets and clever tricks given to him by Q branch before the mission (a mission Bond completes, ultimately, with nothing but a knife).

Amis brings more political machination into the plot than was common under Ian Fleming, a reflection perhaps of the changing times. Published in 1968, Colonel Sun came out at a time when the West and the USSR were getting along (more or less), and the perceived threat to freedom and peace had moved on to Asia and the terrorist cells of the Middle East and Europe. Underneath it all, however, is the classic Bond plot of an unexpected third party trying to frame England and the Soviets for a crime against the other. Colonel Sun moves quickly, with interesting twists and plenty of action. Bond has typically good local support in the form of beautiful Adriadne and crusty old Litsas, and while Colonel Sun himself is perhaps a bit underused, he’s still a satisfyingly slimy villain without going too far afield into the realm of Fu Manchu-esque Yellow Perilism (though no one would claim his portrayal is without typical racist overtones). The only weak character is M, though as an older man, recently infirm and then drugged and dragged around, it’s perhaps understandable. Also, Amis is on record as having hated M, so this is also the author’s chance to humiliate the cantankerous spymaster.

Ariadne is a good female character for a Bond novel, tough and competent and not in need of Bond saving her (well, he does, but only after he himself has been saved by a different woman, so I think that cancels out). Of course, this is still a Bond novel written in the 1960s by a man, so there are certain attitudes about sexual assault that are predictably problematic. After Sun has captured everyone, he offers Ariadne up for rape by his minions. Afterward, when she has escaped and Bond asks her how she is, she shrugs it all off as if rape is really no different from being socked in the jaw. To the book’s “credit,” at least it doesn’t rape and kill her as some motivating factor for Bond, but that still doesn’t mean the entire idea isn’t handled with a bit more shrugging than it deserves. But then, this is a series of books that includes The Spy Who Loved Me, where the young female point-of-view character (written by a middle-aged British guy) muses at one point that all women like to be semi-raped.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Colonel Sun has the most explicit descriptions of Bond’s amorous liaisons yet written. Fleming may have lived like Bond, but he was still too polite to get overly descriptive with sex. Amis, always keen to kick a taboo around, isn’t writing porn here, but he certainly takes James Bond farther into the realm of, say, a Nick Carter spy novel than the series has previously dared venture. It’s some consolation that, in the end, Bond’s sweet love doesn’t result in Ariadne abandoning her Communist beliefs or begging to come with him to experience the freedom and sexy secret agents of the West. She remains true to her cause. All things considered, she is a fair enough female character, and she’s not plagued by the thing where writers of spy thrillers will describe a female agent as tough and competent, then write page after page of her crying, being terrified, or messing up the job (we’ll have years of John Gardner Bond novels for that).

Bond himself is familiar and seems more or less like the Bond who would emerge from the emotional wringer of OHMSS and YOLT, with time to recover down in Jamaica. He’s a bit more haunted, and perhaps his feelings about killing and about his job are a bit more complex and conflicted (multiple times he goes out of his way not to kill someone, even when that person is identifiably an enemy). When Colonel Sun was initially published, the reviews were mixed, and many of the negative ones focused on Amis’ writing of the Bond character, which they saw as not being in line with the character as written by Ian Fleming. I think many of these critics were thinking of Sean Connery more than Ian Fleming’s James Bond, as the Bond of the novels has always been a complicated storm of emotions—doubt, cunning, ruthlessness, uncertainty, charm, and vulnerability. In terms of character evolution, Colonel Sun is a much more fitting follow-up to You Only Live Twice than was The Man with the Golden Gun.

It was inevitable that Amis’ entry in the Bond canon would be a lightning rod. It is, in many ways, similar to the film On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the sole Bond adventure starring George Lazenby and which was, for years, regarded as an oddball black sheep. Like that film, Colonel Sun has undergone reconsideration in more recent years. Some of the criticism is not without merit. The plot is labored in places, and Bond depends on the luck of a last-second rescue even more than usual. But claims that the plot eschews the realism of Fleming’s novels and enters the preposterous realm of the films are entirely unjust—or did these critics forget that You Only Live Twice disguised Bond as a Japanese man chasing after Blofeld, who has sequestered himself away in a poisonous suicide garden where he strolled about in full samurai armor?

The plot of Colonel Sun is straightforward, the action fairly grounded, and the ultimate goal of Colonel Sun and his crew is not outside the realm of plausibility, at least by the standards of the espionage novel. Although it was a bit shaky in the initial pages (Amis has a tendency to refer to James Bond frequently by his full name, a quirk that is, thankfully, abandoned once the story really gets rolling), Amis hits his stride once the action moves to Greece, and rather than this being a “pale imitation” of Fleming or a weak example of Amis, it’s a satisfying adventure fully deserving of the James Bond lineage.

Despite mixed reviews, the book was a success (it’s not like Fleming himself didn’t get mixed reviews all the time). All signs pointed to Kingsley Amis writing a follow-up. He even had a plot in mind, with Bond on a train through Mexico. Colonel Sun was based in Greece because Amis had recently been there on holiday; the prospective Mexico setting was for the same reason. It would also enable Amis to express his personal distaste for Acapulco. It was rumored that the next book would feature the death of Bond and an end to the series as a whole. Amis joked (one assumes) that Bond was to be killed by a bazooka-wielding bartender. But a bit of confusion here, a bit of complication there, and in the end no second Bond adventure from Amis was to be.

In time, Colonel Sun was mostly forgotten, allowed to go out of print, and chalked up by many as a curiosity—the George Lazenby of the Bond literary world. Its disappearance was not total, however. The movie For Your Eyes Only, though ostensibly based on the short story of the same name as well as another of Fleming’s short Bond stories, Risico, features action partially set in Greece and an ally whose background is very much that of Colonel Sun‘s Niko Litsas. In 2002’s Die Another Day, the plan was initially to use Colonel Sun as the main villain, albeit with a nationality swap from Chinese to North Korean. Since that would have necessitated paying additional royalties for the use of the character, however, the film made up its own guy and petulantly named him Colonel Moon. Excepting a couple of novelizations of the movies, the Bond literary franchise went into hibernation for the 1970s. It was over a dozen years before someone put ink to paper and wrote a new James Bond novel. That writer was John Gardner (not to be confused with John Gardner, the American author who wrote Grendel), and the novel was 1981’s License Renewed. But that is another story.