A Portrait of the Archaeologist as a Young Man

Inspired more by the Young Indiana Jones Chronicles than the movies, The Peril at Delphi brings Indiana Jones to the printed page

Indy, Henry, follow me! I know the way!”

And so, give or take a line, did the Indiana Jones trilogy ride off into the sunset. Or so we thought at the time. What started in 1981 with Raiders of the Lost Ark — which, if pressed, I may very well name as my favorite movie (it’s that or Casablanca) — and then continued with the imperfect but still enjoyable Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, wrapped in 1989 with the release of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. It was a fitting conclusion to the series, balancing humor and adventure with heart and thrills. Yes, it left some questions unanswered — what the heck happened to Marion — but by and large, it was a fitting swan song for America’s favorite two-fisted, globe-trotting archaeologist, Dr. Henry Jones, Jr.

In March of 1992, The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles debuted on the ABC television network. As the name makes plain, the series told the story of Indiana Jones as a teen and young man (and occasionally a boy). Soldier, spy, world traveler — the show was meant to be an educational program for teens and young adults, and as is usually the case with such shows, young Indiana Jones manages to meet just about every famous person he could during the 1910s-1920s, which is sometimes a bit much. And speaking of a bit much, that’s how ABC felt about the show’s budget. It was a massively expensive undertaking, and the fact that it was aimed at kids when the core Indiana Jones audience that had grown up with the film was in college, meant that it garnered low ratings. It was canceled in 1993. Except for a few made-for-television movies created by stitching episodes together, it would be a long time before audiences saw Indiana Jones in action again on any screen, big or small.

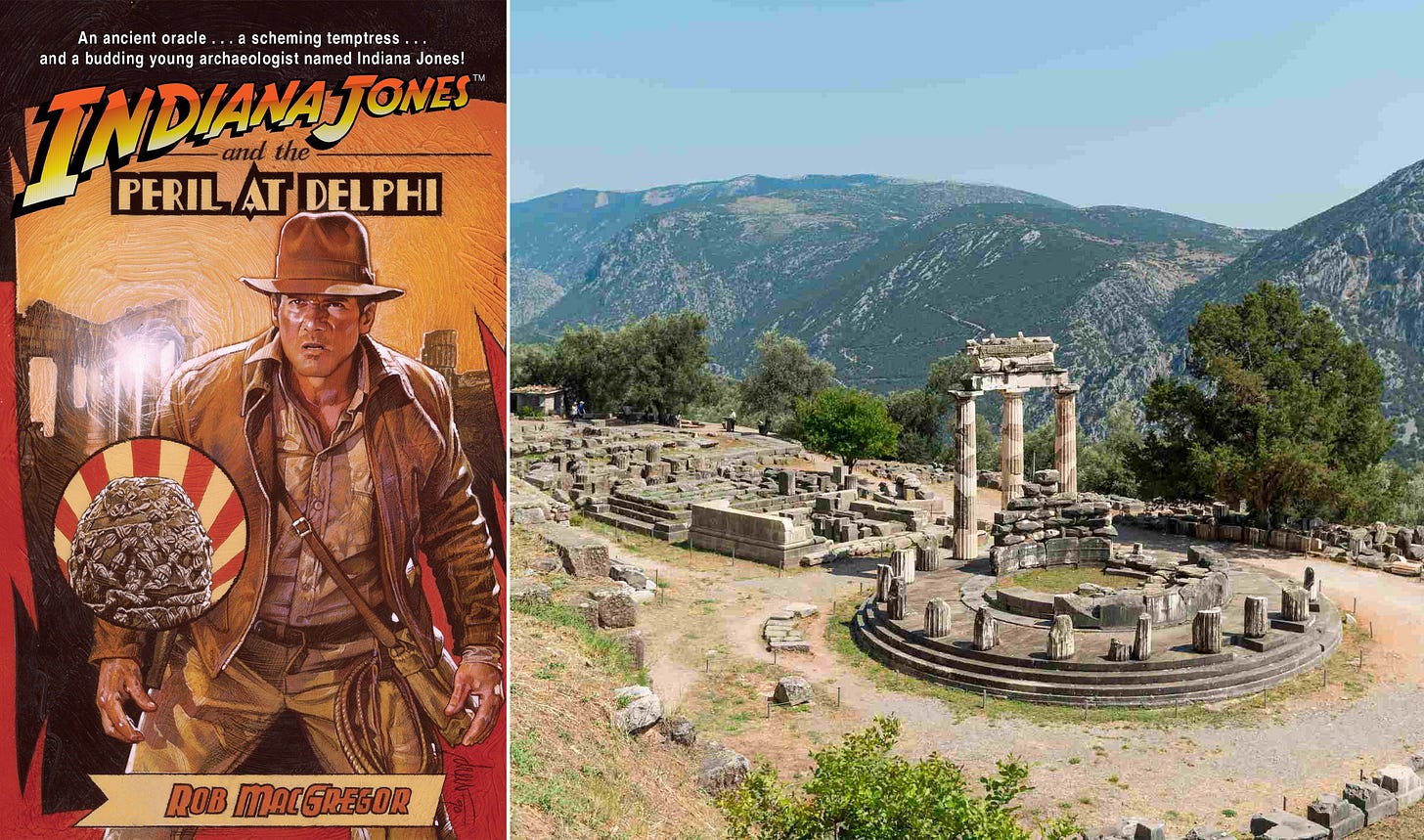

However, sandwiched between The Last Crusade and the first episode of the Chronicles, there was Indiana Jones and the Peril at Delphi.

After the movies wrapped, and while the series was in development, Indiana Jones co-creator George Lucas decided he wanted to commission a series of Indiana Jones novels. He turned to author Rob MacGregor, who had penned the novelization of The Last Crusade. MacGregor had expressed mild disappointment that much of what appeared in the novelization ultimately had to be cut from the film for time and to achieve the tighter focus desired by director Steve Spielberg. Thus, MacGregor was excited about the opportunity to dig deep into the world of Indiana Jones. Obviously, there were a lot of stories that could be told. But Lucas had a set of restrictions he placed on MacGregor. For starters, the books should be prequels, not sequels, to the movies. Second, they should be, like the soon-to-debut TV series, educational and aimed at a younger audience. None of the grit and gore of the movies (that stuff was always Spielberg’s thing). Third, MacGregor did not have permission to use any of the characters from the movies other than Indy and Marcus Brody. Others could be mentioned, but they could not appear.

Lucas had similarly hedged his bets years earlier when he hired Alan Dean Foster to write the first Star Wars continuation novel, Splinter in the Mind’s Eye. Foster was told to write a book that could serve as a potential sequel to Star Wars, but because Lucas did not expect the movie to be a huge hit, what Foster came up with had to be able to make for a cheap movie (no space stuff, for starters). And since it was assumed Harrison Ford would not return for a potential second movie, Foster was not allowed to include the character who would emerge as the most popular in the series (and, of course, be played by Harrison Ford, the same man who played Indiana Jones). Subsequent Star Wars novels would also operate under restrictions planned primarily to make sure nothing in the books would conflict with what might be on screen in a sequel. As Lucas, Spielberg, and Ford had not completely ruled out a fourth Indiana Jones film, it was simpler to keep MacGregor within certain boundaries. No worries, because the life of Indiana Jones, even before the movies, was full of thrills.

So MacGregor, who was himself a well-rounded globetrotter with a keen interest in history and archaeology, set about the task. In 1991, he delivered Indiana Jones and the Peril at Delphi, set in 1922 (with a prelude in 1920) and featuring an Indiana Jones fresh out of college and dutifully studying for his future career as…a linguist. Obviously, that career trajectory is not going to last, and by the end of the book, Indy has course-corrected toward archaeology, if of a somewhat unorthodox fashion. The book begins in 1920, on the eve of Indy’s graduation from the University of Chicago. He’s a dedicated student but not without a wild streak. He and his pal, Jack Shannon, are avid fans of barrelhouse piano this dangerous new music called jazz. He’s also not above a bit of mischief, as evidenced by a brief run-in with a sleazy bootlegger and a stunt he pulls for graduation that involves hanging effigies of the Founding Fathers to make a nuanced political point. Although his favorite history professor turns Jones in, the man also argues for clemency, allowing the young rascal to graduate and continue his studies in Paris.

Two years later, we catch up with Indy in Paris, studying with a beautiful (as is always the case) professor named Dorian Belecamus who, despite Indy having no experience in archaeology, enlists his aid on an excavation in Greece. A recent earthquake has further damaged the ruins of the Temple of Apollo, once home to the legendary Oracle of Delphi. But the quake has also revealed a new artifact, an ancient tablet, stuck midway down a deep crevasse. Against the advice of Jack Shannon and his own better judgment — everyone gets the feeling that there’s more to the trip than Dorian is letting one — Jones agrees, if for no other reason than he was in a bit of a funk anyway, and he’s sort of hot for teacher.

It seems everyone was right to have misgivings about the excursion. Jones is promptly seduced by Dorian, but his happiness about that turn of events is offset by the number of mysterious people who keep popping up to stare, menace, and occasionally attempt to kill him. Before too long, young Indy is caught up in dual plots to resurrect the glory of ancient Delphi and assassinate the king of Greece. He also drinks a lot of retsina (a traditional Greek wine made from pine sap).

As a pulpy adventure, Peril at Delphi is pretty entertaining. As an Indiana Jones adventure, well, there’s not a whole lot of the Indiana Jones we know (and are led to expect by the cover art, which depicts Raiders-era Indy), and there’s not a whole lot of the action one would expect. It’s also very light on the mystical, but then, so was Raiders until the big ghost jamboree at the end. MacGregor errs on the side of education, per George Lucas’ decree. However, while that means this book is a lot more talking than it is an adventure, MacGregor delivers history lessons about ancient Greece (and hot jazz) in an entertaining fashion, so it all goes down pretty easily.

It’s not all kid stuff, either. Jones does get lucky with his older teacher, after all, and he does a fair bit of drinking. And “light on action” doesn’t mean there’s no action. Indy does at least have his whip, after all, and he gets to dangle from a rope in a pit while holding a torch, which is one of his favorite things. As the book progresses toward the conclusion, it goes in for a good many fistfights and car chases. After all, you can’t expect action-adventure Indy to spring out of college fully formed. As a light adventure to help Indy kick off his archaeology career, it’s a breezy good time that fulfills George Lucas’ wishes and also manages to be a fun foray into the early days of Indiana Jones.