Computer Love

The Pioneering Digital Synth Music of Doris Norton

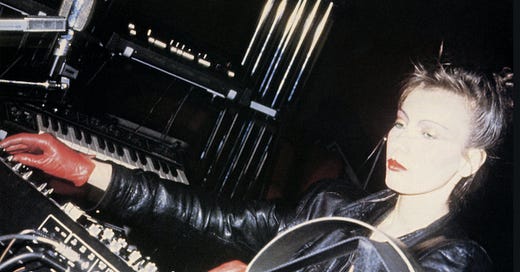

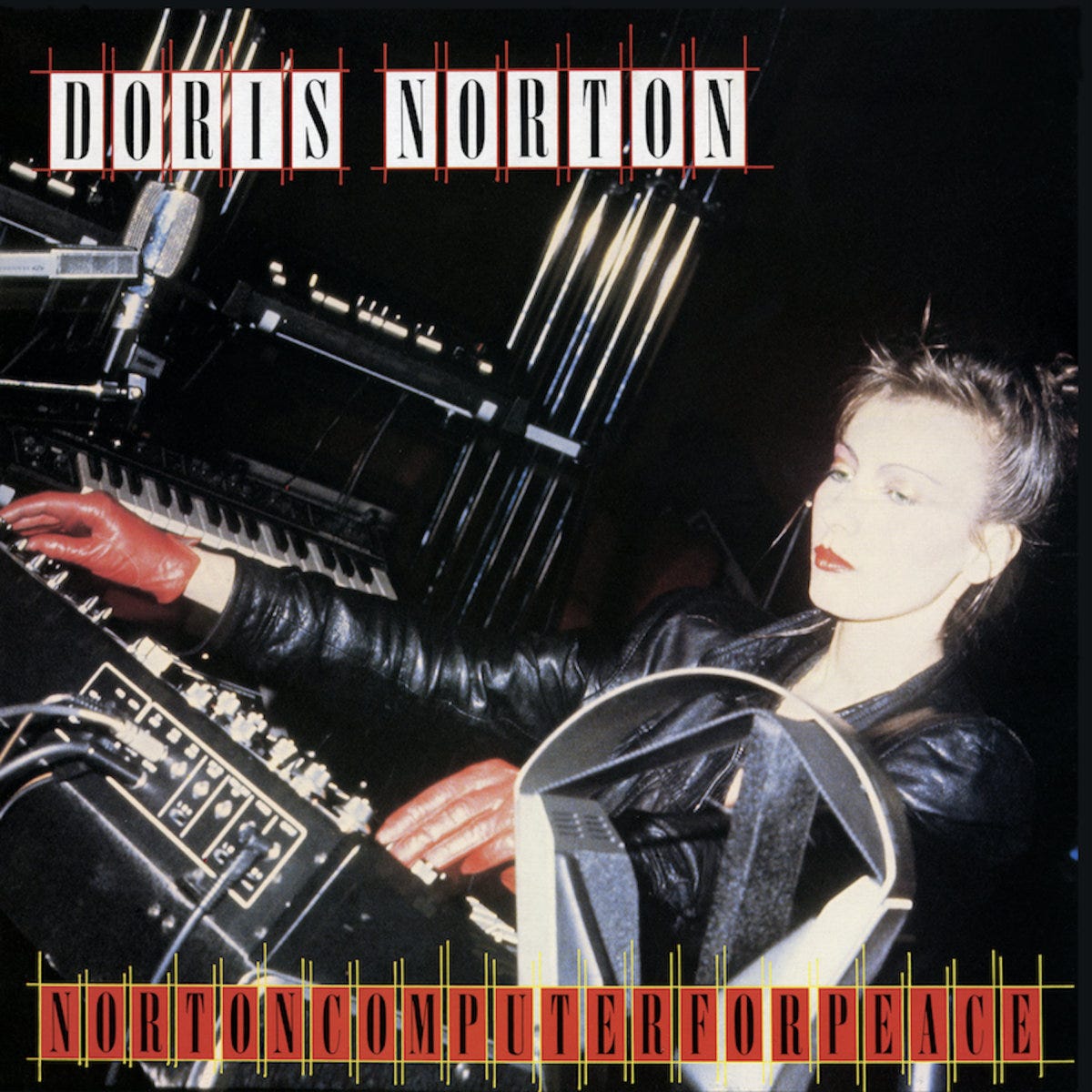

In the world of electronic music pioneers, Doris Norton is one of the bridges between the synthesizers of the 1970s and the personal computers of the 1980s. She was born in London but enjoyed most of her success in Italy. An early advocate of using the first Apple Macintosh computers to create music, and later a collaborator with IBM, Norton came up in the prog krautrock sound of the 1960s and '70s (she even played in a band, Jacula, later known as Antonius Rex). Originally released between 1983-1985, Norton Computer For Peace (1983), Personal Computer (1984), and Artificial Intelligence (1985) form a sort of trilogy in which Norton explored the musical capability of these strange new Mac computers. For Norton, working on a personal computer was ideal. She preferred the solitude of it compared to recording in a studio.

All three albums were reissued in 2018 by Mannequin Records, an Italian label founded by Alessandro Adriani and Carlo Cassaro and which specializes primarily in techno music—something Norton became interested in in the 1990s and creates along with her son, Anthony, who records under the name Rexanthony. Given their origins as display pieces for the potential of computer-based musical composition and production, all three albums trend more experimental than they do New Wave or synthpop, even though those are the dominant styles of which one thinks should one be thinking about electronic music from the 1980s. Given how far the broader genre had progressed by that decade, the music on Norton's three albums sounds a bit more primitive. While analog synths and the music composed to take advantage of them had been evolving for decades, using a personal computer was, in many ways, stepping back to the early days of electronic music. Norton's peers are the pioneers of the 1960s and early 1970s more than they are her contemporaries in the 1980s, although one can certainly find parallels between her compositions and Yellow Magic Orchestra; hip hop and electrofunk artists like Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force, Twilight 22, and Jonzun Crew; the 8-bit video game scores created by someone like Hip Tanaka for Nintendo; and artpunk bands that experimented with synthesizer minimalism (I'm thinking the Comateens' "Ghosts" here, only without the guitars, although who would want the Comateens without Oliver's fantastic guitar?).

So, more avant-garde than danceable, although in the right cyberpunk setting, a track like "Norton Computer For Peace," which opens her 1981 album by the same name, could definitely inspire some angular, minimalist moves. On it, she not only uses the computer to generate beats and synthesized sounds, but she also experiments with the vocoder to deliver that sweet, sweet robot voice we fans of 1970s and '80s electronic music love so dearly. The album's second track, "The Hunger Problem in the World," opens with a militaristic beat before launching into a frenzy that sounds like a computer's version of a jazz pianist just going off. "Don't Shoot at Animals" has a much thicker sound (and incorporates sampled bird and nature sounds), with lots of layered digital synth creating a very 1970s futuristic, cinematic science fiction landscape that would have been very much at home on Piero Umiliano's phantasmagoric Tra Scienza e Fantascienza. At 10 minutes long, it's nearly triple the length of most of the other tracks and gives Norton room to create a mesmerizing digital soundscape that explores multiple tempos and styles while remaining a cohesive whole. "Warszawar" is another dancier number, albeit dark. It would work perfectly in an off-kilter Italian cult film from the same time. Norton Computer For Peace closes with "Iran No Ra," a multilayered slice of electronic exotica that sounds even more like something Goblin would have created for an Italian cult film soundtrack, or John Carpenter's Escape from New York theme.

Although largely instrumental and thus somewhat abstract, it's a very political album, with most songs being inspired by Norton's horrified reaction to the many violent conflicts that defined the 1980s: martial law in Poland, the Iran-Iraq war, the Salvadoran civil war. These menacing aspects of tyranny manifest as martial, marching beats.

Computer Programing But Make It Neon Decadence

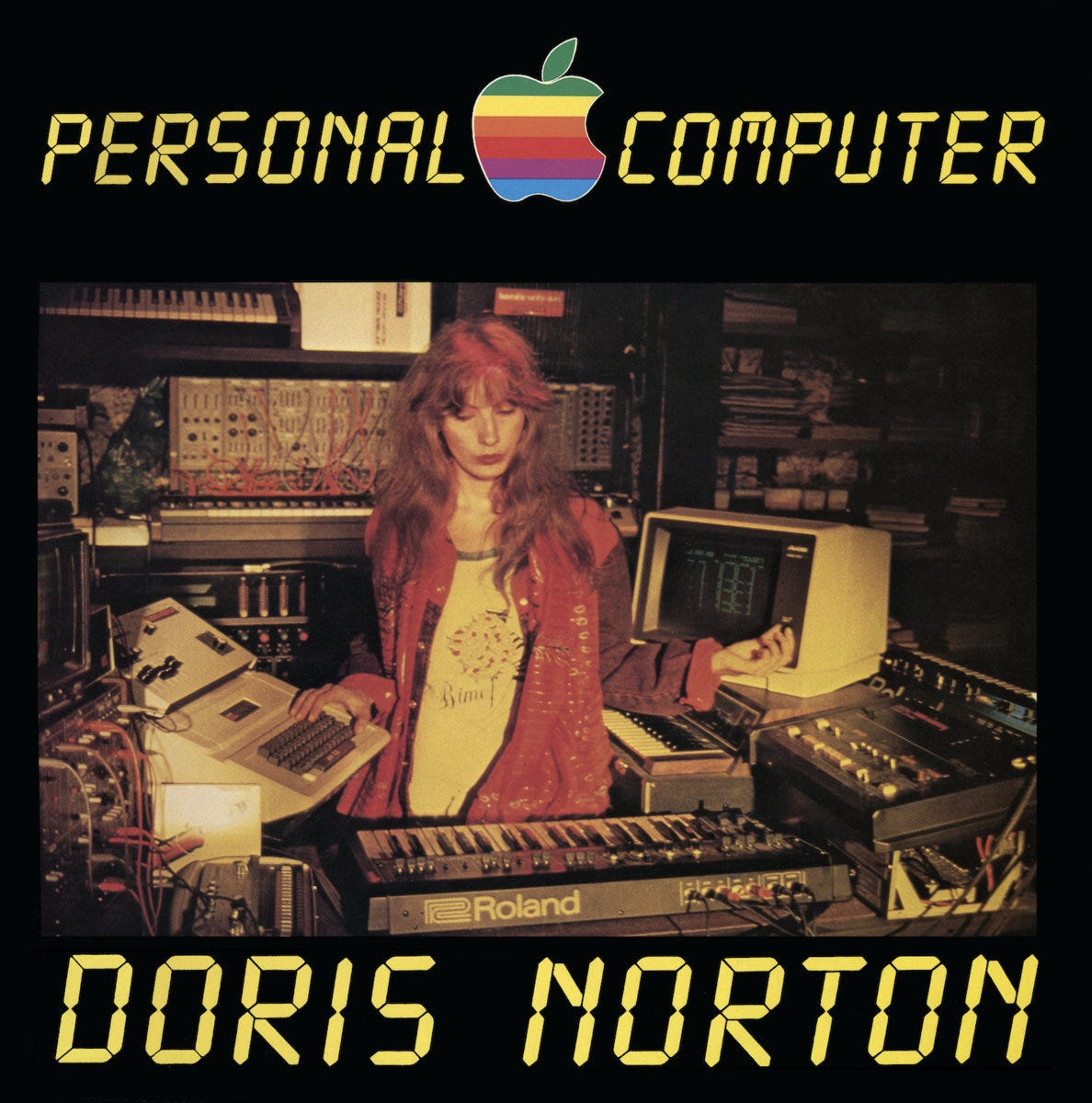

A year after Norton Computer For Peace, Doris Norton sat down at a brand new Macintosh keyboard to create Personal Computer, a release for which the Apple computer was so instrumental that their logo is included front and center on the album's cover. It's notable that 1984, a year heavily influenced by time catching up to George Orwell's chilling 1949 dystopian novel—was the year Apple debuted their still-famous "1984 commercial," introducing the Macintosh computer to the world during the Super Bowl that January.

From the get-go, the album is more accessible than Norton Computer For Peace and showcases greater synthpop sensibilities and structures. The DJ definitely spun the title track at whatever discotheque was frequented by those two computerized new wave women briefly glimpsed in TRON (or, not as icy cool, maybe Buck Rogers could teach it to that 25th-century band). It's still pretty experimental, at the same time, and not quite up to keeping step with what was being done with analog synthesizers. 1984 was a strong year for analog synths in pop music. That year, we got everything from Thompson Twins' Into the Gap to Frankie Goes to Hollywood's Welcome to the Pleasuredome and Bronski Beat's The Age of Consent. By comparison, Personal Computer still sounds more 1970s, but it's a noticeable progression in terms of software capabilities from her previous album. It sounds much more at home alongside synth-driven Italian movie scores. I'd say put it in a Bruno Mattei film and it'd feel right at home, but I'm not sure Doris Norton deserves the cruelty of being associated with a Bruno Mattei film (I say as someone who adores Bruno Mattei films).

She's drawing inspiration from the very tool she's using to create the music, with tracks sporting on-the-nose names such as "Apple Software," "Parallel Interface," and "A.D.A. Converter." That last one, which is also the last track on the album, best captures what's happening on Personal Computer. It's funny to think of analog synthesizers being regarded by more traditional musicians as the cold, emotionless tools in the 1970s, and then by the mid-1980s, they're the warm, quaint tradition being challenged by music created fully in-computer (and that someday this whole movement births Hatsune Miku). A.D.A. (or ADDA.) converters enabled a musician to plug an analog synth into a computer and turn it into a digital file that could then be further manipulated via software. Norton uses A.D.A. conversion equipment to capture the sounds of organs, analog synths, animals, and other items that she can then process and manipulate to create samples and beats along with what was done natively within the computer.

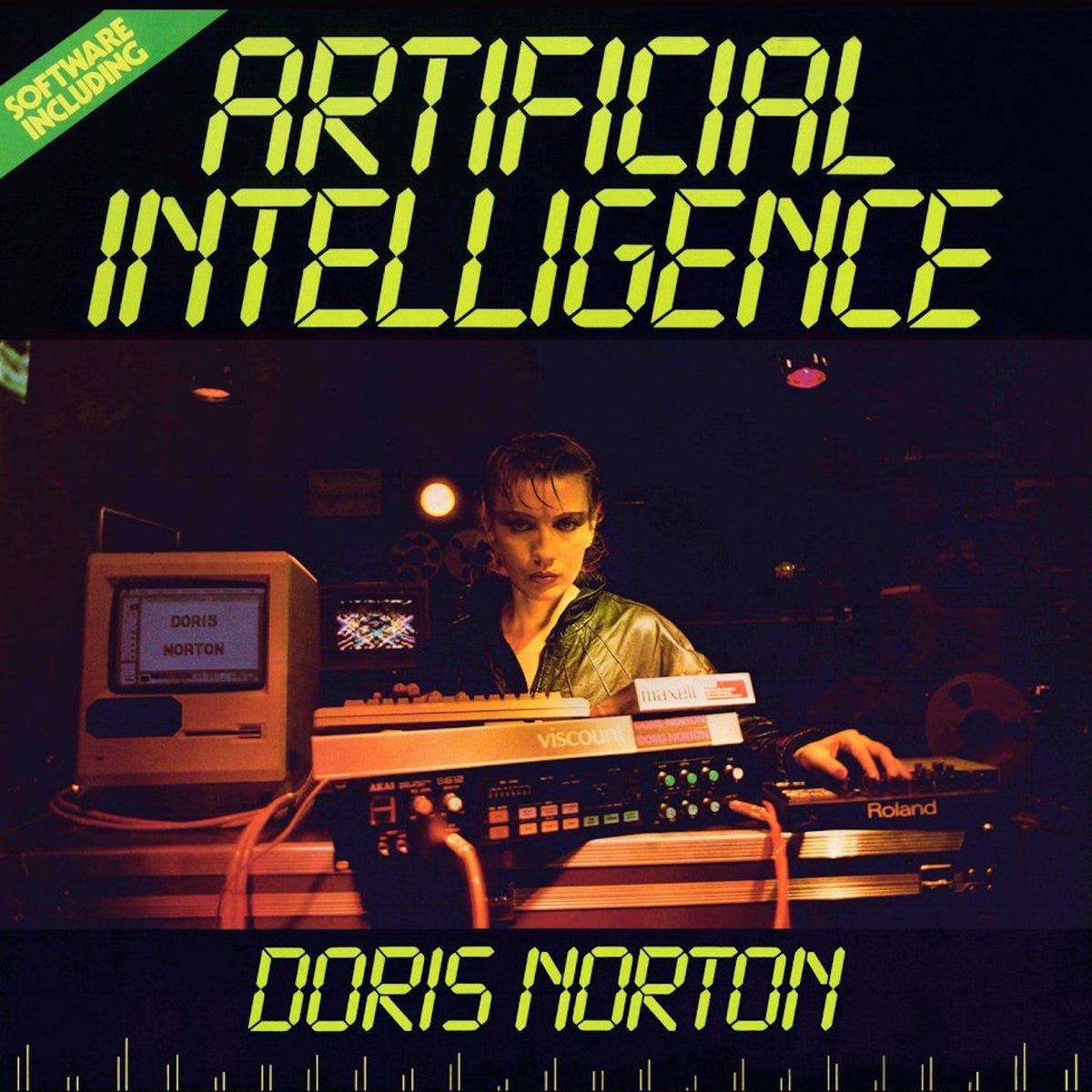

POV: You're Not IN a Simulation; You ARE a Simulation

Norton's third album in this not-exactly-a-trilogy, Artificial Intelligence, is by dint of its title a synthesis of everything that motivated her as a musician. In a 2012 interview with It's Psychedelic Baby, Norton explained that from her early days fiddling with synths, sequencers, and computers, she was motivated by biology. "In the beginning," she tells interviewer Klemen Breznikar, "my main questions were how music has control over biological equipment and all the matter itself, how [the] brain receive, stores and process music information." She also explains that her music was influenced by "heart rate sound, brainstorming, and electroshock signals," which for me calls to mind Kraftwerk's Tour de France, in which the group constructs songs based on the rhythmic breathing and tempo of cyclists as well as the equipment that goes into training and monitoring their performance, such as the track "Elektro Kardiogramm."

Norton explains that her music is the result of an interest in "anthropology, biology, biochemistry, [and] maths," and that interplay between the biological and the digital, the human and the computer, and one becoming the other (in whichever direction you chose) is a core concept at the heart of the study of artificial intelligence. Granted, the reality of AI today was still largely science fiction when Norton's Artificial Intelligence came out in 1985. It builds on the work of the previous albums, showcasing once again the continuing advances of what could be with a computer as a musical "instrument" and Norton's own comfort and familiarity with the software.

The distance between analog synthesizers and digital creation continues to narrow. Artificial Intelligence really splits the difference between synthpop and the electronic avant-garde. One track you feel like you could get up and dance (or at least wear mirror shades and walk through an arcade or underground club), and the next sounds like Norton is channeling a group like the Residents, all eventually leading us to something approaching the soundtrack of the video game Portal 2. This is a musician still exploring new territory and vacillating between structured pop and just seeing what could be done, regardless of how weird and discordant it may sometimes be. As such, Artificial Intelligence is maybe of more interest to fans of electronic experimental music than pop. If you were making electrofunk and hip-hop, her music would have been a goldmine of beats to sample.

Doris Norton joins a growing number of women—Johanna Magdalena Beyer, Daphne Oram, Delia Derbyshire, Bebe Barron, Suzanne Ciani (and I only leave Wendy Carlos off the list because she actually did achieve some degree of fame, comparatively speaking)—who were pioneers in electronic music and largely denied their due during their original go-round but are thankfully being rediscovered, reissued, and revered for their groundbreaking contributions. For me, it's exciting to listen to someone stretching their legs and finding out where the limits of this new technology may be and then figuring out how to get beyond them.

Addendum: I've searched but, as of this writing, cannot find detailed info on what software Norton used. MacroMind MusicWorks was the Mac standard audio software in 1984. Norton's relationship with Roland and some of the song titles help us figure out other tools at her disposal: Roland Juno 106, JX 3P, and Synth Plus 60 synthesizers. I would love to know the set-up. For the record, today you can recreate those classic Roland synth sounds with plugins and even (not for free) cloud-hosted digital versions.

References

"Doris Norton interview," Klemen Breznikar. It's Psychedelic, Baby, September 2012.

"The story of electro pioneer Doris Norton," Aurora Mitchell. Resident Advisor, August 2018.