Forever and a Death: The James Bond that Almost Was

Pulp fiction legend Donald Westlake's James Bond screenplay that became a not-James Bond book

In 1995, it had been nearly six years since the release of a James Bond film. That film, 1989’s License to Kill starring Timothy Dalton, hadn’t exactly set the box office on fire. Nor had the previous film, The Living Daylights, and A View to a Kill was no prizefighter at the box office. In the 1990s, no one was sure the world cared about 007 anymore. However, the franchise had been in much the same situation in the 1970s, when the lackluster performance of Roger Moore’s first two outings (Live and Let Die and The Man with the Golden Gun) met with critical and box-office indifference. Back then, they figured that the game was over. It had been a good run, but post-Sean Connery, with Vietnam raging, maybe the time for a smug, wisecracking secret agent had passed. They decided to give it one more go, pulling out as many stops as they could as sort of a last hurrah, before folding up the operation and fading into pop culture history.

To everyone’s surprise, The Spy Who Loved Me, was a massive hit. Suddenly, where he had once been on the brink of death, James Bond came roaring back. Years later, EON Production’s Barbara and Michael Broccoli, who inherited the series from their father Cubby, were wondering if they could pull off the same trick. So despite the relative failure of Dalton’s two Bonds, they set about making GoldenEye with a new actor and few guarantees. Pierce Brosnan, the man chosen to inherit the license to kill, was a TV actor of moderate popularity at best. Director Martin Campbell, had a filmography of little note composed mostly of TV work and early ’70s sex comedies, including Eskimo Nell and The Sex Thief. Sure, Pierce had Remington Steele, which had a whiff of secret agency about it, and The Sex Thief was about a wisecracking cat burglar, but Brosnan and Campbell were far from a sure thing. As is the way of things in the movie business, while GoldenEye was filming, producer Jeff Kleeman was making plans for the sequel…just in case. If GoldenEye was successful, they wanted work on the follow-up already underway. And if it was a failure? Well, few things are as affordable and disposable as the rough draft of a script. Kleeman, for whom working on the Bond franchise was a childhood dream come true, was tasked with finding a writer. His first thought was of another of his childhood heroes.

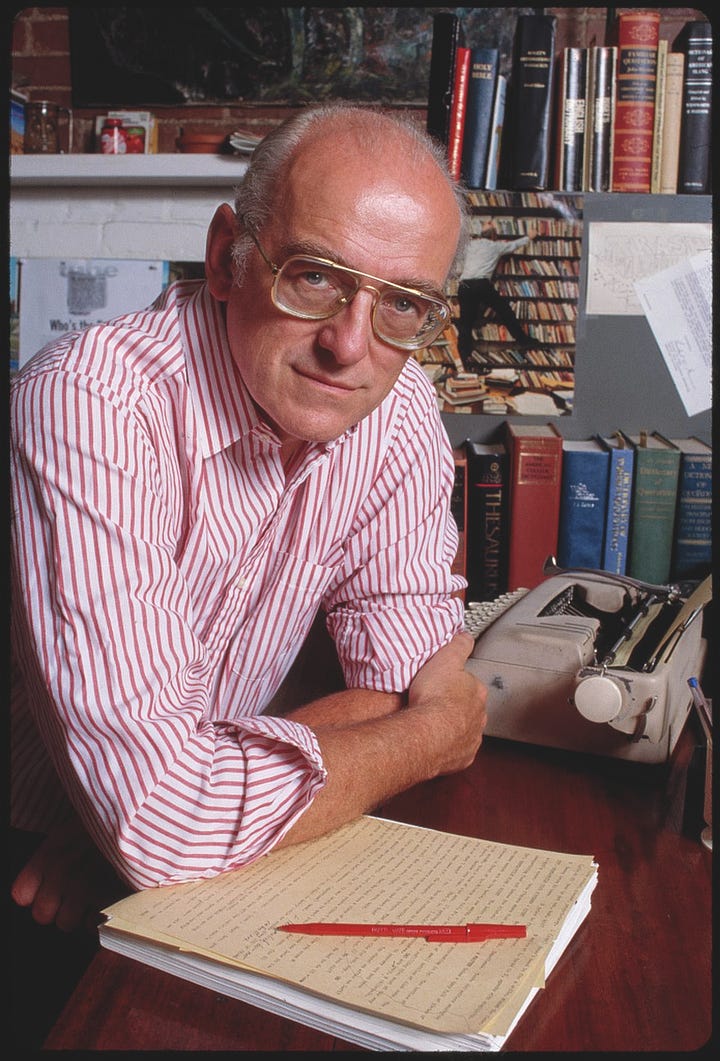

Donald E. Westlake was best known for his “Parker” books, a series about a mercilessly cool, amoral criminal. Following hot on the heels of Parker’s popularity was John Dortmunder, a more light-hearted series about a thief always involved in some comically convoluted caper. Between the two of them, Westlake was well-versed in most of the personality traits of Bond and the action beats of a Bond movie. He had little experience writing screenplays, preferring to simply sell the movie rights to his books (including the neo-noir masterpiece Point Blank from 1967, starring Lee Marvin) and be done with it, but the screenplays on which he’d work (including 1990’s The Grifters, based on a novel by Jim Thompson) had usually worked out all right. The Grifters even earned Westlake an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. When Kleeman pitched the idea of writing the next James Bond movie, Westlake was enthusiastic and threw himself into the project with gusto.

He offered a couple of different pitches before they settled on one revolving around the handover of Hong Kong from Great Britain to communist China, a political event that had a lot of people nervous and would, given that the film would likely be released in 1998, be one of the first times a Bond film aligned with current geopolitical events. Westlake’s pitch had Bond and a female Chinese agent joining forces to stop a madman who wants to destroy Hong Kong. Kleeman was excited by it, and the two were toiling away in the revision and refinement phase when GoldenEye was released. To everyone’s relief and more than a few surprises, GoldenEye was a hit. Unfortunately for Westlake, whose writing process was somewhat slow, that meant the next Bond film was getting fast-tracked, and he simply wasn’t able to adapt his writing process to the demands of the schedule. Additionally, EON started to get cold feet about the Hong Kong storyline, fearing that it would result in the film being banned from mainland China, even then a major source of box office. As a result, Donald Westlake and James Bond parted company amicably, the idea of a Westlake-written Bond film becoming just another piece of forgotten “what if” Bond lore.

A tiny bit of Westlake’s work snuck into the final version of the film that became Tomorrow Never Dies. For example, Bond is paired with a Chinese agent (played by Michelle Yeoh). But the bulk of Westlake’s ideas never surfaced in the film (although Hong Kong during the Handover did become the setting for a later James Bond novel, Raymond Benson’s reasonably entertaining Zero Minus Ten, published in April of 1997). However, it turned out that Westlake, who died in 2008, hadn’t been entirely willing to let all that work go to waste. He’d taken his treatment for the Bond film and turned it into a novel. Not a James Bond novel, exactly, since he didn’t have the right to use James Bond, but something new that used the same premise: a wealthy industrialist with a grudge plans to destroy Hong Kong, and an intrepid adventurer must stop him. In 2017, Hard Case Crime — a publisher with a knack for uncovering lost and unpublished works of pulp crime fiction — got permission to publish the book. At last, Donald Westlake’s ideas for James Bond saw the light of day in the form of Forever and a Death.

If you don’t know that backstory, you wouldn’t necessarily guess Forever and a Death has anything to do with James Bond (though the villain, Richard Curtis, is cut from the same cloth as self-made Bond maniac-businessmen like Goldfinger and Hugo Drax). The hero, if you want to call him that, is a construction engineer named George Manville who works for industrialist Richard Curtis as the head engineer on a project meant to use controlled, violent waves to turn unstable land into something usable (in the case of Curtis’ plan, for a custom-made island resort). During a test at a coral reef off the Australian coast, the project is interrupted by an environmentalist named Jerry Diedrich who really has it for Curtis. Kim Baldur, an activist on board Jerry’s ship, decides to take matters into her own hands, diving out to the test sight to make herself a human shield. Unfortunately, no one gets Kim’s message, and when they discover her presence at the test site, it’s too late to stop the explosion that triggers the waves. The test goes through and is successful…except that it kills Kim.

Except that it doesn’t kill Kim. It just injures her severely. She’s fished out of the water by Curtis’ crew. For the ambitious industrialist, this creates a problem. Kim’s death due to the negligence of Diedrich would help Curtis discredit the thorn in his side. But a live Kim? Much less of an asset. As far as Curtis can see, there’s one easy solution: make sure Kim, who everyone thinks is dead anyway, winds up that way. But murder just for the sake of avoiding construction delays? That seems a little much, even for a driven man. It turns out more is going on with Curtis than building islands for resorts. He has another use in mind for the process, a use far more destructive and deadly that will help him settle a grudge he has against Communist China. Alas for Curtis, Manville discovers that Kim is alive, and he’s less enthusiastic about murder than his boss.

There’s a lot of fun to be had with Forever and a Death, but it’s also full of problems. First and foremost, there are too many points of view. Minor characters get whole chapters devoted to them doing things like seeing a guy walk out the front door. Some of these side characters make an interesting contribution, but others are meandering and have the whiff of filler about them, or something that might have been cut out had the manuscript gone through one more phase of editing. It results in a crowded, disjointed narrative that never quite finds a rhythm. Just when it seems like things are going to click, Westlake shifts focus to some random thug, stretching out what could have been taken care of in a paragraph into a full chapter (or more). Second, George Manville, disappears for a substantial portion of the book, cooling his heels while imprisoned in one of Curtis’ compounds. It’s as if Westlake loses interest in his hero in the middle of the book and casts around for a character he finds more interesting. Given that Westlake’s two most popular characters were criminals, it’s surprising then that he lands on Richard Curtis.

Curtis emerges as the most interesting, fleshed-out, and complicated character. He’s a guy with a huge chip on his shoulder, but he’s no master criminal. He bungles almost everything, and his attempts to right the situation usually make it worse. He’s queasy about the depths to which he finds himself sinking and struggles to justify it to himself in feats of increasingly desperate mental gymnastics. It is, in short, a pretty believable look at an egomaniac whose fantasies of revenge get him in over his head. Westlake seems on firmer ground writing a conflicted villain than when he’s sketching the more traditional good guy, though when Manville is present in the book, he’s a satisfyingly complex and interesting character as well. Like Curtis, he’s a guy with few qualifications to be an action hero, who finds himself thrust into the role nevertheless. Whenever Westlake pauses long enough to concentrate on a character, the development is quite nice; it’s just that concentration isn’t one of Forever and a Death’s strengths.

Completing the trio of main characters is Kim Baldur, the intrepid if reckless environmentalist who finds herself in the middle of everything. At the time Westlake was writing Forever and a Death, the James Bond novels were coming off the final John Gardner book, Cold, published in 1996. Gardner’s books were a mixed bag, but his female characters were uniformly awful. He thrived on introducing a woman, describing her as competent, then spending the rest of the novel undermining that description and portraying her as an utter buffoon. Westlake’s Kim Baldur is a substantial improvement over what was happening in Gardner’s books. Granted, for Westlake and at that point, it was the movies far more than the novels that were the primary influence. Still, those working through the novels will find Kim a welcome respite from Gardner’s aggressively bad female characters. She is, like Curtis and Manville, a smart person dealing with something far beyond anything she’s prepared to deal with. Since Manville disappears for a large swathe of the book, Kim gets a nice stint to operate on her own, without fulfilling the role of “damsel in distress” (though of course, she gets there eventually and, naturally, falls in love with George Manville).

Even when the central scheme gets to be a bit much, Westlake (a master of convoluted schemes) keeps everything moving so quickly that one hardly notices. That, ultimately, is the saving grace of this book. If the lack of focus sometimes comes across as authorial ADD, it also means that, if nothing else, something is always happening. The action jumps from Australia to Singapore and Hong Kong, and even though this Bond story has been de-Bonded, I appreciate that it ends with a classic James Bond commando raid. For Bond fans, Forever and a Death is a novel diversion. For Donald E. Westlake fans, it’s a footnote. But it’s a fun diversion, if inessential, and a reasonably entertaining footnote. How often does structural engineering save the day? Actually, probably pretty often now that I think about it. Like many a Bond film, Forever and a Death‘s shortcomings are as obvious as they are numerous. And like many a Bond film, those shortcomings end up not mattering all that much.