La Dolce Vita for the Berlusconi Era

Rome, Regret, and Paolo Sorrentino's La grande bellezza

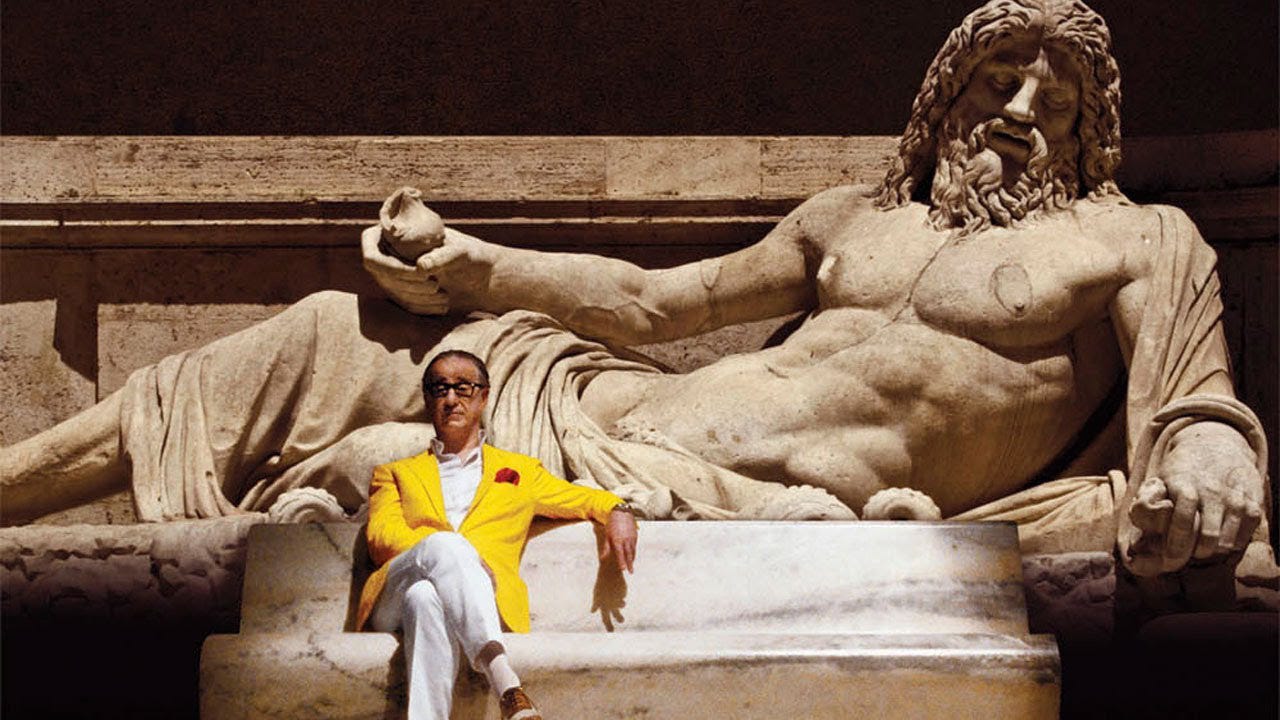

We first meet lifestyle journalist Jep Gambardella amid the thumping techno and drunken revelry of a lavish rooftop party. Through it strides Jep, resplendent in his stylish suit but feeling out-of-place amid such bacchanal. But Jep has a problem. At the age of 65, standing in the middle of the pageantry of Roman nightlife , he feels a bit foolish, even though he’s still a desirable guest. It’s not nightlife that regards Jep as too old to partake in its frivolous revelry; it’s Jep himself.

Nor is Jep condescending toward or dismissive of this desperate, wild life. Although frivolous, Jep is genuinely affectionate and thankful for the good times and is hesitant to let go of them. There is value, after all, in something that gives us pleasure, no matter how shallow it might be. However, although quick with an inviting smile, a companionly arm around the shoulder, or a heart-felt raising of the glass, Jep’s beginning to wonder what the hell he’s doing at his age still strutting around to booming electronica at four in the morning. His time among these revelers is coming to an end, and he’s not sure what comes next.

“La Dolce Vita for the Berlusconi era” many call director Paolo Sorrentino’s La grande bellezza (aka The Great Beauty). The temptation to compare it to Federico Fellini’s classic is irresistible. Few articles about the movie — this one, obviously, included — get through the first paragraph, or even the article title, without mentioning La Dolce Vita. Sorrentino shares with Fellini an eye for extracting the grotesque and absurd from superficially elegant and polished surfaces. Both films’ main character is an impeccably tailored journalist who covers that curious intersection of artistic pretension, bourgeois indulgence, and failure; where people still regularly go to society salons and desperately try to maintain their sense of self-importance and grandeur, where bankrupt aristocrats ignore their financial woes and rub shoulders at posh clubs with the starlet, the has-been, the never-will-be, or the never-was.

There are indeed similarities. However, there are also important differences between Marcello Mastroianni’s young Marcelo Rubini and Toni Servillo’s aging Jep Gambardella. Both cover wild society events and trendy art world happenings, but Marcello does so from the periphery of sophisticated society, while Jep finds himself in the middle of it and is often its center of attention. Despite having only written one novel in his life, Jep’s career as a high-living journalist writing about other high-livers has garnered him considerable adoration. He’s not a laughingstock or the “creepy old guy” still hanging out at parties meant for the young. His presence is welcome and wanted. As he states himself, he wasn’t striving to be the guy invited to all the best parties; he wanted to be the man with the power to ruin the party if he didn’t show.

As narcissistic as that might sound, it’s tempered by the fact that Jep only wants the ability to ruin a party. He doesn’t actually ruin them. This is the second difference between him and Marcello. I doubt Marcello would have ever become the warm, loving—if still imperfect and occasionally cruel—individual we see Jep to be. There is a cynical streak in Marcelo that is tempered, although not entirely absent, in Jep, and a bitterness that’s not present in the older man even when he is delighting in taking the piss out of artists with inflated opinions of themselves.

We stroll through the life Jep has built for himself as it begins to dissolve and as he begins the search for something else. He has, as they say, reached the age where life stops giving us things and starts taking them away—or so it seems upon a superficial glance. Amid the bouts of ennui, however, he still discovers things worth celebrating. His editor, a tough woman who appreciates Jep’s no-nonsense sense of humor, proves a solid, endearing friend. He strikes up a poignant friendship with Ramona (Sabrina Ferilli), a middle-aged dancer. Their time together provides the film with many of its sweetest moments, best among them being when the two abandon a fancy art show full of the city’s most prominent movers and shakers in favor of going with a friend who happens to possess keys to a number of famous museums, landmarks, and palaces, which Jep and Ramona tour in joyous solitude. Old eyes, older people, old familiar things—but still bursting with newness and secrets still to be discovered.

Their relationship is a subversion of the “aging man seeks renewed life by dating a younger woman” cliche. For starters, she’s not that young. Younger than Jep, sure, but still in her forties — not old but no longer young. Jep does not look to her for salvation or burden her with the demand (as so many films do) that she do the work of inspiring him to rekindle his love of life. She is not his manic pixie dream girl. He is not her lonely and distant man who needs saving. They’re two companions, walking the same path at slightly different phases—just two people who become friends.

While The Great Beauty sometimes analyzes the lives of Jep’s friends, he rarely stoops to judging them. After all, they’re just flawed people like him, trying to find their way. Instead, his observation of their lives, of their triumphs and tragedies, is a microscope he uses to examine himself. He’s aware of his own shortcomings and is perfectly happy to acknowledge them, though he’s never wracked with guilt or regret for the decisions he has made. He has squandered his talent as a writer, but he has also led a pretty good life regardless.

This amused self-awareness tempers the harsh advice he sometimes delivers. His friend Romano (Carlo Verdone), for example, is a frustrated playwright struggling to adapt a story by Gabriele D’Annunzio for the stage. Jep, who speaks from a position of knowledge as a fellow writer suffering writer’s block (though Jeps’ has lasted for decades), tells Romano he’s wasting his time and that he should write something original. Jep’s dismissal of Romano’s great project stings, but ultimately Romano heeds the advice and writes something genuinely moving.

We get the idea that Jep is surrounded by people going through the same transitional period as he himself is and that together they bounce enough support and criticism off one another so that at least some of them will find their way. Whatever solutions are discovered will come from within rather than from some external force such as finding religion or a romantic relationship. Although events lead Jep to ponder his first and only true love, he’s not a man who bemoans the fact that at his age he is still a bachelor. He’s happy to be so, and the film doesn’t force a saccharine, old-fashioned “if only I had a family, I’d be whole” trope on us.

Religion doesn’t offer any answers, either. The film has two major religious characters. The first is a much respected Cardinal on the shortlist to become the next pope, but who Jep discovers to be vacuous and unwise, only interested in talking about the latest cooking techniques and the most sublime ways in which to prepare duck. It’s not a condemnation of religion (nor of being passionate about food) as much as it is an expression of mild disappointment. The second religious character is an ancient, withered nun on the road to sainthood. In her, Jep discovers much to admire—though almost none of it has to do with her Christian faith.

Although Jep’s advice can sometimes be blunt, only once is he truly vicious in his critique of others, and even then it’s after multiple deferments and only couched in the language of what he himself is and how he has failed. This comes at a party when a long-time acquaintance keeps praising herself, her strong Socialist principles, the importance of her art, and the many sacrifices she has made. Jep’s take-down of her is a thing of icy precision and perhaps the film’s most overt critique of Italian society as a whole. Plus, any writer probably knows someone like the friend Jep critiques (or perhaps you are like that person), and there is at least some satisfaction in hearing Jep so effectively yet so politely run down the litany of delusions and aggrandizement behind which the other character hides. Still, even after this uncomfortable scene, we see the two reunite later, seemingly better for having honestly aired that dirty laundry.

Well, there is one other moment when Jep calls shenanigans on someone in a brutal fashion. He is assigned to interview a daring new performance artist, but when he refuses to be dazzled by her studied quirkiness, self-affected strangeness, and nonsensical responses to his questions, he (politely) loses his patience and hammers away at her pretensions. Again though, he doesn’t seem to be motivated by maliciousness or misanthropy. Even when he’s doing things like this, Jep has such affable charm and levity that it’s hard to think of him as mean. He simply refuses, at his age, to be taken in by pretense. He’s seen it all before—but just because you think you’ve seen it all doesn’t mean you should stop looking. Don’t be taken in, but don’t let the fact that some people will try to take you in, obscure that the world is still full of beauty and things worth loving.

The museums Jep walks through and the ruins of ancient Rome are inspirations for the future, not refuges from the present. “What’s wrong with nostalgia?” one character asks Jep. “It’s all that’s left for people who have given up on the future.” Although they remember it, often fondly, Jep and La grande bellezza are not looking to relive the past, however. Jep isn’t wondering “What if I’d done things differently,” but rather is asking himself “What do I do next?”

Modern cinema has an homage problem, a “love letter to…” addiction that pushes many writers and directors to revel in the past, to try to recreate whatever film, whatever feel, or whatever genre they loved in their youth. In moderation, this is fine. Modern voices mimicking voices from the past can still bring something new to the table, some new form of expression or modern twist. But often, we find ourselves merely aping what came before, and doing so in such quantity that it becomes at the expense of discovering our own voice. Comparisons between The Great Beauty to La Dolce Vita are not undeserved, but Paolo Sorrentino is doing something more than writing love letters to Fellini. This is a film that is, at least in some way, about coming to terms with nostalgia, of appreciating the past while not getting misty-eyed for it (characterized most overtly in the film by Jep’s remembrances of a romance from his youth) or dwelling on it to the point where you disregard the present and abandon the future.

Sorrentino and cinematographer Luca Bigazzi guide Jep with a deft hand and an attention to composition, color, and detail that is all too rare in the chaotic films of today. It’s as gorgeous a film as has ever been made, taking great advantage of Rome’s character, lighting, and tailoring (Jep’s suits!). It’s willing to sit and think for a spell and let the images on the screen speak for themselves (Jep walking through ancient ruins, or along the coast and seeing the hulk of the Italian cruise ship Costa Concordia, which in 2013 was still capsized off Isola del Giglio in Tuscany). The use of music in the score is also masterful, creating a tapestry of the old and the new, from raucous techno anthems to quiet, contemplative classical.

Sorrentino is not as difficult to comprehend as some of the Italian masters with whom he is often mentioned. His narrative, while not plot-driven, is not as scattered as that of Fellini, whose narrative particularly in La Dolce Vita is constructed to overwhelm and confuse, much as the events of the nights overwhelm and confuse Marcello. Sorrentino strolls rather than careens. His, after all, is a calmer Rome than that of via Veneto in the 1950s and ‘60s. Nor is he as bleak and impenetrable as Michelangelo Antonioni. He’s occasionally esoteric, but his film is never unapproachable. It doesn’t wallow in melancholy, though certainly there is something bittersweet to all that we behold. Despite all that happens, at the end of La grande bellezza, one is left feeling uplifted, inspired, and as willing to reopen one’s eyes to the world.

Toni Servillo turns in a grand performance. When he needs to be broad, he is broad, but for the most part, it’s a subtle, charismatic, and moving acting job. Servillo disappears entirely into Jep. He has a face made for playing this sort of man and skill at bringing us to an emotional point without becoming maudlin. Even when he’s being cranky, it’s hard not to love Jep. As he drifts through this contradictory city of mad artists, dreamers, rooftop parties, and secret treasures, Servillo frequently has a smirk on his face, as if to say to the audience, “Can you believe we get to do this?” And it is “we” who get to do these things since Jep is happy to bring us along. He circulates through the upper echelons of society, but he is no exclusivist. Performance artists, movie stars, supermodels, internationally famous party DJs…he knows them all, and they know him, but he’s just as happy—perhaps even happier—with old drug addicts, world-weary strippers, riff-raff, and weird guys with keys to off-limits courtyards. Indeed, despite his high society acquaintances, it’s often with the working class (or thanks to them) that Jep experiences his most sublime moments. He’s aware of the charmed life he’s led. He just has to figure out where it leads him next.

Jep might be unmoored and facing an existential crisis, but he’s not a man for whom the world has soured. As the film’s title suggests, even in a crumbling Italy surrounded by people who once created profound works of art and culture but are now content to sit on the couch (as director Paolo Sorrentino describes Italian culture during the Berlusconi years), there’s still much to admire, to enjoy, and to find beautiful. Marcelo in La Dolce Vita might be fun to spend a wild evening with, but he’d eventually get moody or overly acerbic and kill the vibe. Jep, however, one could be friends with for decades. His eyes are old, but age has not made the world a dimmer, duller place. If anything, age has opened Jep’s eyes wider to the world around him, even if he’s unsure of his place in it.

If one scene best encapsulates the spirit of the movie (alongside Jep and Ramona’s midnight tour of museums), it’s the scene in which Jep stumbles across an incongruous giraffe standing in the middle of a deserted amphitheater. It turns out to be the property of one of Jep’s old friends, a stage magician who is practicing his latest act, during which he will make the giraffe vanish. In a moment of self-pity, Jep asks if the magician might make him disappear, a suggestion the magician laughs off.

“It’s just a trick,” the magician explains. Jep is momentarily distracted by the arrival of another friend, and when he turns back around, the giraffe is gone. The moment at which a smile of such childlike joy crosses Jep’s face as he raises his arms in the air is just exquisite. The simple wonder of a vanishing giraffe trick can bring one to happy tears.