In the years after World War II, American products flooded a world hungry for something other than slaughter and pain. With so much of Europe and Japan left in ruin, it was challenging for locals to fill the void themselves. But America was there, ready and relatively unscathed. French filmgoers flocked to American crime dramas. Many French observers noticed that the films made before the war were different than the ones made during and after. In the United States, where the flow of films had been steady, the transformation was gradual and as a result, not noticeable. France had been sealed off from these films during the Nazi occupation, so the sudden return after years of deprivation made the changes more evident. The plots were more complex. The characters were now morally ambiguous, flawed, even broken. Sometimes even kind of evil. The themes were darker, even as they were made under the yokes of the Hays Code and wartime monitoring of entertainment. In 1946, French film critic Nino Frank gave the new mood a name: film noir.

It’s no shock that this ambivalence would manifest in entertainment. The 1940s, into the ’50s, was a time of contradiction in the United States. It was meant to be a return to “normal” after the war—an experience so profound that nothing could ever return to the normal of before the war. It was a period of financial growth and stability paired with anxiety about the new atomic age and the need to figure out America’s role as a global superpower with an arch-enemy. It was a time of nostalgia and conservatism punctuated by the rising struggle for racial and gender equality. America was buttoned up and proper, but sexual experimentation was blossoming, especially among the new suburban population who left the cities in search of space and community and often found a feeling of isolation and alienation.

Noirish creative expression wasn’t limited to film and detective novels. Before and during the war, the dominant style of music in America had been big band swing, with country only just beginning to make inroads on a national scale. Pop jazz vocalists such as Bing Crosby, Sinatra, and the Andrews Sisters lent the sound its voice. After the war, stretching out into the early 1960s, a new generation of musicians began exploring new forms of expression. Big bands became small quartets and quintets. The Andrew Sisters handed off to sultry femmes such as Julie London, Peggy Lee, and Eartha Kitt (Billie Holiday transcended it all). Music became something you went to listen to, the players someone you went to see, rather than being a backdrop for dinner and dancing. Swing gave way to bebop, and then to post-bop and cool jazz. And somewhere amid the swirl of experimentation, some artists started blending jazz, blues, rural country, and something new to come up with what eventually became known as rhythm and blues; and later, rockabilly and rock ‘n’ roll.

Like noir, the definition of R&B is nebulous. A variety of styles can fall under that umbrella, and you’ll rarely get people to agree on where the porous borders are that separate R&B from rock from blues to rockin’ jazz to exotica, to say nothing of sub-sub genres like Las Vegas grind, popcorn, tittyshakers, crime jazz, and burlesque beat. Who was a crooner, who was an R&B wailer, who was a torch singer? Best to say, rather than lapse into dull debate about genre and technical notes, it’s up to the listener, and it’s more fun to enjoy the music than it is to fret about the label you place on it. Take, for instance, slow grind. Not so much a distinct style as it is a feeling or a mood. You may not be able to say what it is, but you know what it is when you hear it. A style of music that has to do with late hours and smoky joints, close dancing and sweat and something just a little feral. Sinful and sinister. Bars on the county line, at the edge of town. Lyrics that explore dark topics—heartache, lust, loss, violence, drifters (lots of songs about drifters)—without being coy about them. A dark reflection, the underbelly of all that “best foot forward” American optimism which, it turns out, wasn’t being shared by everyone.

Lonesome Drifters and Death Row Dolls

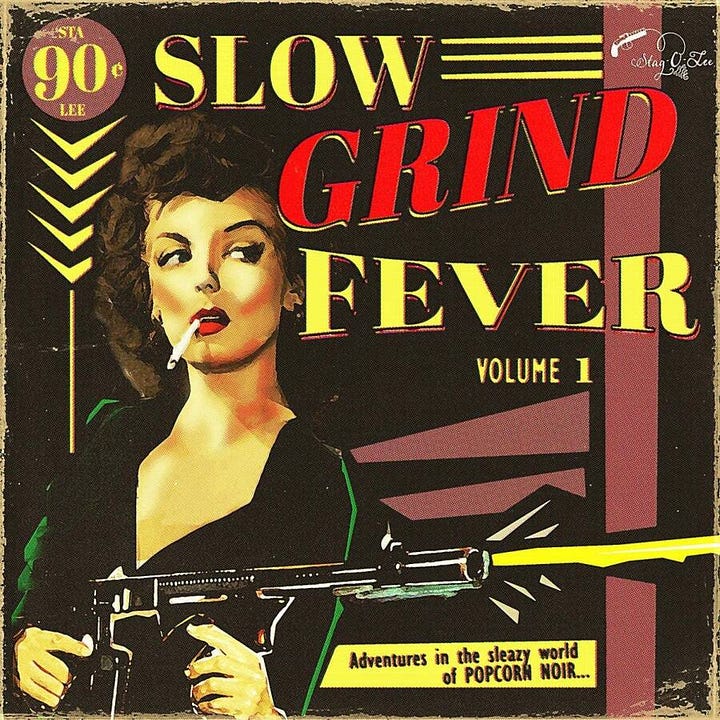

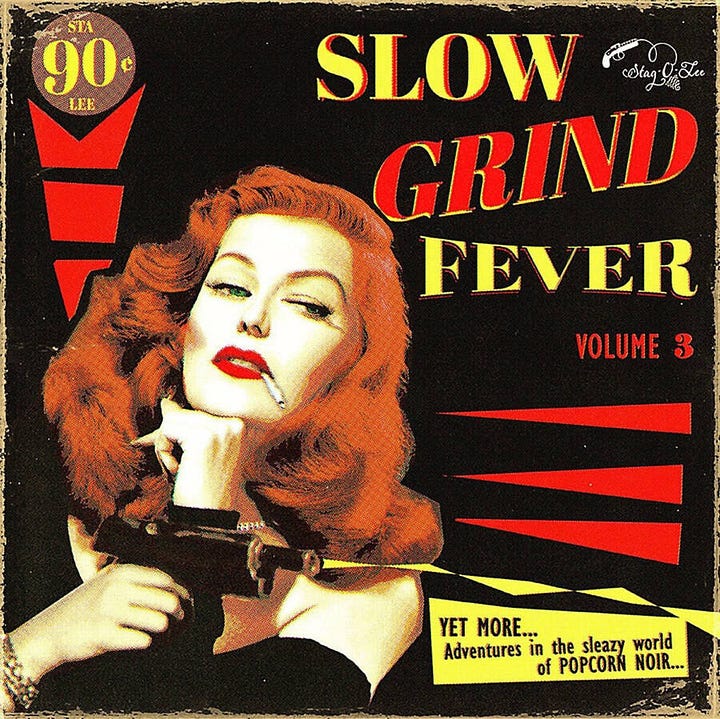

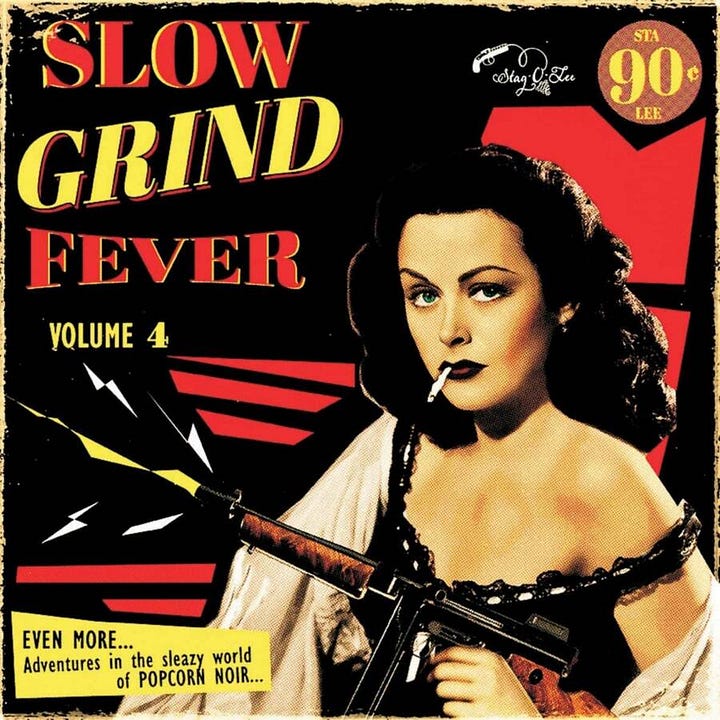

The Slow Grind Fever series evolved from a themed dance night put on by DJs and record collectors DJ Richie1250, Mohair Slim and Pierre Baroni in Melbourne, Australia. Like the French recognizing noir, many of the most dedicated chroniclers of bygone American music are from other countries (where would the history of rockabilly be without Japanese fans and Germany’s Bear Family Records? For the longest time, only Norton Records was keeping the fabulous flame burning in the US), so it’s no surprise that one of the best explorations of this shadowy branch of American R&B has been undertaken by Australians. It’s often easier to see these things from afar. As their slow grind nights gained popularity, they struck a deal with German record label Stag-O-Lee to release some of the music they spun at their events. The resulting series is currently up to 10 volumes, released as separate LPs or two-volume CDs. I’ll be looking at the first four. They are fascinating collections of creepy, crawly R&B in a minor key, some songs and artists obscure, others major hit makers in their day.

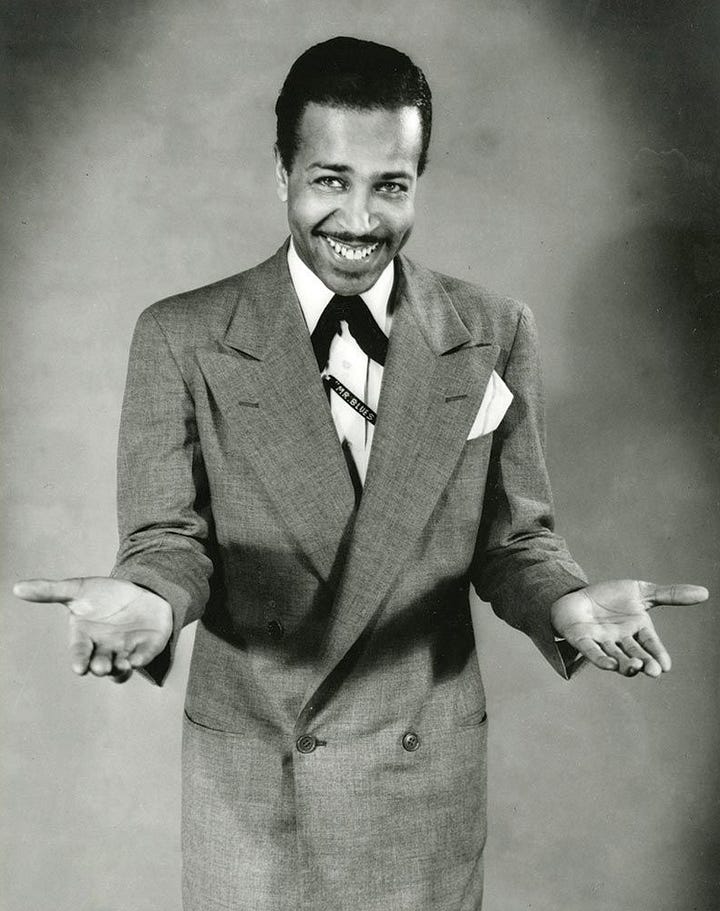

Volumes one and two open with “Whale of a Tale,” a hit from sax player Wynonie Harris, one of the most important R&B pioneers and an important, though often ignored, part of rock ‘n’ roll’s origin story. The song is a perfect encapsulation of the sounds to follow—minor keys, moaning and wailing, growling sax, and a big, primal beat made for dancing close and dirty. The second track, “Hawk,” is a sinister slice from Bill Haley & His Comets, best known for the seminal rock ‘n’ roll song, “Rock Around the Clock.” Here, the lyrics frame competition in love as a violent struggle between predatory birds.

Ernie Fields, an artist who never became a star but was a staple performer both before and after the war in big bands as well as small groups, turns in “Workin’ Out,” a prowling instrumental that introduces a twangy surf guitar vibe to the rockin’ piano and horns, making it the perfect beachside crime anthem. Lavern Baker is the first woman to step onto the slow grind stage, in a duet with doo-wop legend Jimmy Rick’s mega-bass of a voice. Women working in the slow grind style truly bring the flame to torch singing. Helen Grayco, who was married to and often performed alongside Spike Jones, delivers a scorchin’ prison lament with “Lilly’s Lament (Cell 29)”, and Sylvie Mora brings some sultry exotica with her version of “Taboo.”

Then comes Nina Simone, the “high priestess of soul,” with “The Gal from Joe’s,” recorded for her 1962 album, Nina Simone Sings Ellington. Simone was a controversial artist for all the right reasons. Headstrong, proud of her Black heritage, dismissive of the pop recording industry, and always interested in the underground. In the 1960s, she was a vocal proponent of the Civil Rights movement, culminating (but by no means ending) with her 1964 album, Nina Simone in Concert, which featured the song “Mississippi Goddam,” a reaction to the murder of Medgar Evers in Mississippi, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham that killed four Black children. Although the tune is deceptively jaunty, the message is one of frustration, exhaustion, and rage. Simone would go on to be one of the great voices of the movement, recording several protest songs that also became hits (or were banned in certain places), including “Four Women,” “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” and a version of “Strange Fruit,” the horrifying, haunting song about lynching made famous by Billie Holiday. Even “The Gal from Joe’s” has a subversive edge to it.

There are a few songs that became go-to slow grinds. “Fever” is probably the best-known and most recorded, which may be why this volume avoids it (it’ll come up later, though not the famous Peggy Lee version). A close second is “St. James Infirmary,” a depressing number made for nodding along to in brooding contemplation. The origin of the song is lost to the mists of time, but Louis Armstrong made it famous in 1928, and it’s been a standard ever since, receiving many different twists and interpretations. Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway did it. Betty Boop did it. Oingo Boingo and the White Stripes did it. The version here, from 1961, is by blues legend Bobby “Blue” Bland, who delivers an arrangement powered by blues guitar and, perhaps in salute to Louis Armstrong, a dash of New Orleans jazz.

There are plenty more scorchers where those came from. Dee Irwin’s “Anytime” isn’t a deep song judged by the lyrics, but the emotion in the song is fantastic. Jericho Brown’s “Lonesome Drifter” has a finger-snapping beat, but the down-on-his-luck protagonist, with his coterie of ghostly female backing vocalists, is hardly the happy-go-lucky wanderer of “King of the Road.” Blues shouter Big Maybelle howls through “Rain Down Rain.” Maybelle’s impact on blues and R&B was so great that one scarcely realizes the brevity of her life. She died at the age of 42, another of the many victims of heroin addiction. Scatman Crothers became a famous voice actor, with roles in the animated TV shows Hong Kong Phooey and The Transformers, but here he reminds people that he knew how to wail, with the “Dead Man’s Blues.” Dick Dixon & the Roommates’ instrumental, “Caterpillar Crawl,” brings a raw rockabilly sensibility, sounding like something Link Wray could have recorded. Barbara McNair was a nice ‘n’ easy vocalist who somehow got seduced into recording the sleaze-beat gem “He’s a King.” Like all of the tracks on this compilation, it shows the diversity in style and performers that can press against one another on the slow grind dance floor.

As with many things, from a vantage point so many decades removed, it can be lost on modern audiences how confrontational and revolutionary certain elements of a song once were. Even Bing Crosby’s Depression-era lament, “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” minds its manners. America’s period of self-denial and reserve was over. Coming off the crisp, clean sound of wartime jazz vocals, where even the most passionate feeling or melancholy reflection was delivered with a certain reserved manner, the naked desire and emotion of R&B and rockabilly was shocking. That unbridled emotion was always in music—no one could reasonably claim the blues, even in the 1920s and ’30s, was chaste and reserved—but it was R&B that pushed it onto mainstream audiences of varying races.

Wynona Carr makes the direct connection between the Garden of Eden and getting kicked out of the Garden of Eden. She was a famed gospel singer (for which she appended her name with “Sister,” like another legendary gospel rocker, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, whose contributions to the foundations of rock ‘n’ roll are even more tragically overlooked than Wynonie Harris) who, despite the religious nature of her day job (and as was the case with many a praying sinner), would slip into slow grind mode from time to time, as she does for the soulful, melancholy “Please Mr. Jailer.” As was said about country music juke joints in the 1940s, the point of Sunday morning was to atone for all the sinning you got up to on Saturday night.

With more spooky background wailing, and another growling lady in the lead, Lorrie Collins’ “Another Man Done Gone” was the young woman’s announcement to the world that she was no longer a child. Collins was part of a popular duo alongside her brother, but when she turned 17, she ditched that life and married a talent manager whose number one client, Johnny Cash, wrote this song for Collins. Larry O’Keefe also keeps things creepy with his exotica rock spooker “Lover’s Dreams,” full of melancholy and bongos, while Johnny Carroll turns in a ghostly slice of misty night with “Bandstand Doll,” a song title that doesn’t hint at how mysterious and gloomy the sound is going to be. That sort of “floating through a nightmare” sound dominates a lot of song songs on the back half of the combined Volume 1 and 2 CD. The mood comes to a dark conclusion with the final three tracks: the languid, melancholy “Summertime” by Santo & Johnny (of “Sleepwalk” fame), Lee Hazlewood’s grim prison dirge, “The Girl on Death Row,” and Eddie Miller’s otherworldly country haunter, “Ghost Town.”

It’s a fantastic collection with a lot of styles, all of them possessing that certain darkness, vitality, and sultry danger. Some songs might be better than others, but none are weak, and as a whole, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better mood setter, whether you’re looking to slide up against someone in one of those dimly-lit wood-paneled joints, take a lonely drive to nowhere as you contemplate loss, or maybe just figure out what to do with that smoking gun.

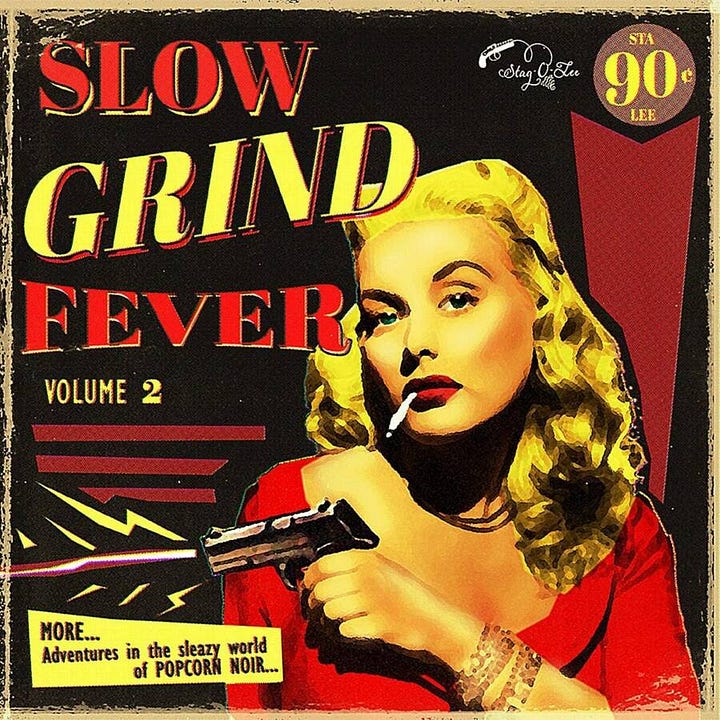

Night Crawlin’ Noir

Slow Grind Fever volumes three and four showcase a wide range of cultural influences. With more bands than ever starting in attics, garages, and basements across the landscape of 1950s/1960s America, and with more access to inexpensive recording facilities (even if it was just a mic and a mixing board in a gas station), record stores were flush with wild material, much of it recorded by artists with no chance of fame beyond playing a few local gigs. The important thing was that music was being made, and musicians were flexing their creative freedom. Rarely had commercial pop been so willing to be weird and sinister. In the steamy world of the slow grind, these emerging styles manifested in several intoxicating, often bizarre tunes. The mood isn’t as consistently dark—but you need that diversity of mood for it to be a memorable night, don’t you? It can’t be all skulking in the shadows and animal lust in the hallway. Or, it can, but it doesn’t hurt to pepper that with mystery and romance. The first four volumes of Slow Grind Fever are the soundtrack for the perfect night, from rowdy house party to cramped juke joint to shady strip club to a moonlit rendezvous in the wee small hours. Are you there to kiss or kill? Or kiss and kill? Doesn’t matter. Either way, there’s a song for you on this collection.

The disc opens with the Notes’ “Cha Jezebel,” a classic slow grind accompanied by Latin flair. If there’s one thing slow grind songs like as much as drifters and fevers, it’s Jezebels. The second track, El Torros’ “Yellow Hand,” is the perfect example of the sort of obscure experimentation that was getting a chance—a dizzying mix of tropical exotica, Mexican ballad, and doo-wop with a Native American theme. Where does something like that come from? The El Torros started in ’51 as a group thrown together to entertain their co-workers at a baby carriage factory Christmas party. They stuck with it beyond that toss-away gig, played some local spots in St. Louis, and one night caught the attention of Bobby “Blue” Bland. He recommended them to a label, and while they didn’t become chart toppers, they did get to record.

Among the big names on this volume are the Isley Brothers, whose career spanned decades and who underwent some line-up and stylistic changes, from vocal trio to band, from doo-wop and gospel to funk and rock. “Teach Me How to Shimmy” is the perfect steamy house party slow grinder, recorded a year before their break-out hit, “Twist and Shout.” Other big hits on this volume include the Flamingos’ “I Only Have Eyes for You,” possibly the most recognizable song in the entire “Slow Grind Fever” series. More of a romancer than a grinder, but you can still dance close to it. It’s one of the great dreamy, late-night songs—because it was literally a late-night song, recorded after the singers were roused from bed at 4am.

“Little” Jimmy Scott contributes a similarly dreamy, romantic number hearkening back to the era of crooners but mashed up with doo-wop and delivered in Scott’s distinctive contralto voice. Scott had Kallmann syndrome, which kept him from hitting puberty until his late 30s. This gifted him with both his signature voice and the “Little” in Little Jimmy Scott; he was 4’11” until age 37 when he hit his growth spurt. throughout his career, however, he had one of those voices that, no matter what he was singing, made you believe.

Jay Hawkins before the Screamin’, Howlin’ Wolf, and Elmore James round out the big names on this volume and represent the Chicago style of electric blues emerging alongside and often merging with rock and R&B. As great as it is to hear deep cuts from these masters, the real joy of Slow Grind Fever is the obscure, forgotten, and unknown artists. Like Donna Dee, for example, doing her best Wanda Jackson snarl alongside a primitive-sounding, stripped-down roadhouse backing band. Or Harlem native Varetta Dillard, who sounds like Patsy Cline at her rockingest (which would be “Love Love Love Me, Honey Do”)—but spicier and with a growling sax hanging out with the honkytonk piano, reminding us that the roots of American pop music are tangled, and the divisions into which it would eventually be forced are often meaningless except for marketing. R&B could have plenty of country, and country certainly conjured rhythm and blues.

There’s also the two Yvonnes. Yvonne Fair, a protege of James Brown, is backed by Brown’s band on “If I knew,” a classic slice of soul. It was originally released as the down ‘n’ dirty slow grind flipside of a song so good James Brown would eventually record his own version: “I Got You (I Feel Good).” Yvonne Baker was part of a moderately successful doo-wop group called the Sensations. “Eyes” finds them straying away from the classic doo-wop sound and into that peculiar back alley where R&B meets exotica, with a dash of something beatnik.

Elisabeth Waldo wasn’t known for R&B, but she had a good career in the realm of exotica. A true student of traditional South American music, she released fantastic albums such as Rites of the Pagan and Realm of the Incas which, unlike many of her exotica contemporaries were based more soundly on actual traditional music of South America. She may seem an odd fit alongside the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and the Isley Brothers, but her mysterious instrumental, “Balsa Boat,” is a slice of otherworldly wonder straight from the steamy jungle. You know they get up to it down there, too. It may not be everyone’s slow grind fave, but when you find that someone who will dance to it with you, you know you’ve found someone magical.

Members of the big Harlem Renaissance orchestras used to gather after hours for late-night/early-morning jam sessions where they could shake off the confines of swing and show tunes and go nuts. Cozy Cole was one of those members, playing drums for Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, and later backing up bop pioneers Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. “Bad” sounds like something that would have come out of one of those late-night sessions. It’s weird, raw, dirty, and all over the place, like a swing band got drunk with a conga band, invited some scantily-clad dancers over, and figured, “Let’s see what happens”—which is often what did happen at those all-night sessions.

Two of my favorite discoveries are Bobby Rebel and Duane Eddy. No one seems to know much about Bobby Rebel. Unless there are other 45’s out there waiting to be unearthed, he only recorded once, “Valley of Tears” with “Teardrops From My Eyes” on the B side. As one can guess from those titles, this is a guy who wears his emotions on his sleeve. Another background choir of ghost ladies, along with a twanging guitar and even some strings, lend texture to Rebel’s soulful moaning. Duane Eddy’s “Stalkin’” was probably inspired by the likes of Link Wray, whose signature tune, “Rumble” was released the same year. “Stalkin’” was recorded by Lee Hazlewood, a master of lush, gloomy songs of doom and romance. To get the exact echo and twang he wanted for the song, Hazlewood recorded Eddy inside an empty water storage tank.

And then there’s the Stone Crushers’ “Crawfish”…who writes a song that spooky and sexy about shrimp??? But there it is, with a chorus wailing “crawfish” in a way that ranges from scary to gospel. And I thought Elvis’ “Song of the Shrimp” was weird. The hell?

In 1964, the Beatles hit America, and every band was suddenly plucking out Brit Beat covers. Fun enough, but it washed over one of the most interesting, most bizarre, and most diverse (musically and racially) periods in American pop music, when songs about killers and hustlers and strippers, heartache and murder and loss, sex and lust and love, and yes, drifters and Jezebels, occupied the murkier recesses of an uneasy American mind.