New York is one of the oldest cities in the United States, and its most populous. So it’s no surprise that among our 8.5 million residents are more than a few ghosts. Our ancient (well, for America) brownstones and Revolutionary War mansions, our cobblestone (or potholed to the point of seeming cobblestone) streets, and our occasional nightmarish gambrel rooftops host a number of specters, many of them famous in life, some famous only in death. From the ghost of a Ziegfeld Follies girl to Mark Twain’s House of Death, here are some of my favorite New York haunts.

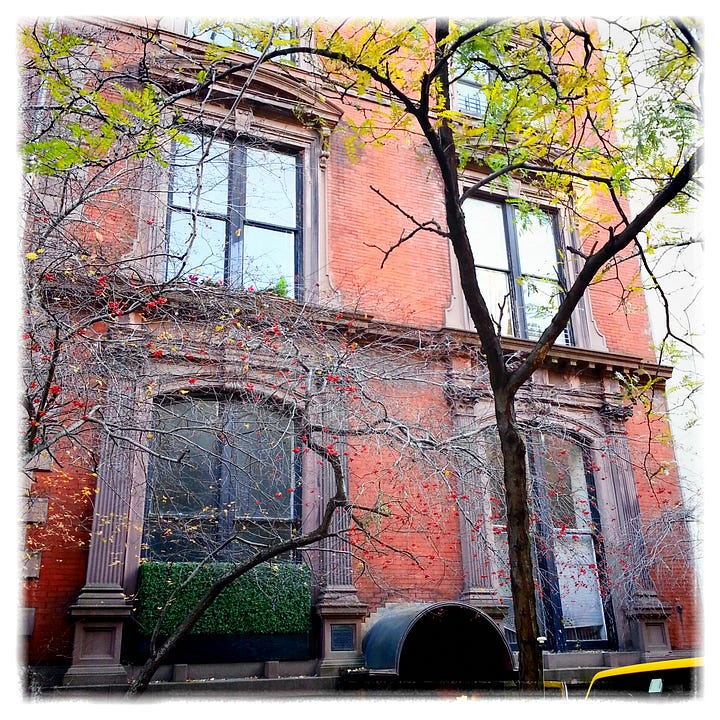

14 West 10th Street – The House of Death

Once the home of Samuel Clemens—Mark Twain if you’re nasty (and I know you are)—this handsome West Village townhouse is also one of the most haunted buildings in New York. Naturally, folks claim the ghost of Mark Twain lurks about the place, no doubt lighting his pipe and reflecting on the time he spent aboard the starship Enterprise with Whoopi Goldberg. Twain only lived in the house for a year, so I doubt his ghost would have much reason to make the trip down from Wave Hill, or Elmira, or Hartford, or any of the other places Mark Twain haunts. In fact, the house already had a reputation as a have for ghosts when the skeptical Twain moved in in 1900 (some say that’s part of the reason he did so). While others claimed it was the resident ghosts who did things like jostle the firewood, Twain outrageously claimed that rats and other urban critters might be a more logical explanation. Can you even imagine? Rats? In New York City??

These days, folks prone to claiming such things claim the house is haunted by no fewer than twenty-two spirits. In 1987, the tranquil looking house—by then converted into apartments—was the site of the murder of young Lisa Steinberg, who was beaten to death by her cocaine-addicted father. The entire block seems to play host to a variety of ghostly lingerers. Emma Lazarus, who wrote “The New Colossus,” is said to still wander the street; she lived at 18 West 10th Street. Writer Dashiell Hammett (The Maltese Falcon) lived nearby at 28 West 10th Street with playwright Lillian Hellman, and Marcel Duchamp moved in a little later. There is even tale that the ghost of Edgar Allen Poe returns to his old home at 17 West 10th Street, where he reportedly lived when he had his heart broken by a rejected marriage proposal. And keeping everyone well-behaved is 14 West 10th’s former neighbor, Emily Post, who lived at 12 West 10th Street.

COS – The Spring Street Ghost

Formerly the Manhattan Bistro, the COS clothing store at 129 Spring Street is home to an old well that became infamous for its role in the first major murder trial in the history of the then-young United States. On December 22, 1799, young Juliana Elmore Sands left her boarding house in the company of her fiancée, Levi Weeks, after confessing to a relative she and Weeks intended to marry secretly. Later that night, locals strolling past the new neighborhood well swore they could hear a woman screaming “Murder!”

On Christmas Eve, a woman’s muff was found floating in the well, and on January 2, 1800, the body of Juliana Elmore Sands was dredged up. Suspicion immediately fell upon Levi Weeks, a well-off man they claimed murder the hapless young working girl in order to get out of marrying her. Week’s powerful family countered public opinion by hiring the city’s most celebrated lawyers: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. In a scandalously corrupt trial, Weeks was acquitted. Juliana’s cousin, incensed by the verdict, allegedly pointed an accusing finger at the victorious Hamilton and proclaimed, ““If thee dies a natural death, I shall think there is no justice in heaven!”

Four years later, Hamilton was dead, shot in a duel by his old law partner, Aaron Burr. Meanwhile, poor Juliana is said to linger around the well, which is now in the basement of COS. When it was still the Manhattan Bistro, plates and glasses were sometimes thrown about, and some say they saw a young woman in a dirty dress covered with moss and vines. The Manhattan Bistro should have consider blaming the ghost for their plethora of 1-star Yelp reviews, persistent cockroach infestation, and C rating by the board of health. Whatever the case, it seems Juliana Elmore Sands got her revenge against…well, the Bistro. It went out of business in 2014, replaced in 2015 by the COS that’s there now. And yes, you can pop in and see the well.

Burr, for his part in the sensational trial, suffered his own unnatural death — penniless, disgraced, and ruined after being divorced by the owner of…

The Morris-Jumel Mansion – The Ghost Clock

At least 35% of New York City’s rich collection of historical locations can be summed up with the sentence, “And here is where Aaron Burr was an asshole to someone.” Not long after the Weeks-Sands scandal, and bearing his portion of the curse, Aaron Burr found his own life in tatters: a wanted man for killing Alexander Hamilton, unlucky in investment, disgraced more times than anyone could manage to count. His ghost pops up all over New York, including his old carriage house, which is now the exquisite restaurant One If By Land, Two If By Sea.

The ghost of another sort of victim of Burr resides in Manhattan’s Morris-Jumel Mansion. Built in 1765 by British loyalists Roger Morris and Mary Philipse (who subsequently abandoned it when the US declared independence), the mansion was the one-time headquarters of George Washington (the Battle of Harlem Heights was fought nearby). It was abandoned after the Revolutionary War. In 1810, Stephen Jumel and his wife Eliza bought the mansion.

Eliza Jumel was a scandalous figure, though much of what was said about her seems to be the product of the men of her time being vindictive toward uppity, independent women. Her husband Stephen was a businessman, though not much of one, and most of the family success is attributable to Eliza. Rumors swirled about her. She was a former Providence, Rhode Island prostitute (in reality, she was the daughter of a prostitute and worked as a cleaning girl). She had been kicked out of France for being too controversial and saucy (she was kicked out of France, but likely for being pro-Napoleon even after his defeat at Waterloo and the restoration of the French monarchy). When her husband returned from France after ruining himself (luckily, Eliza had invested money previously), he was in a carriage accident that cost him his life—an incident during which some people say Eliza sat and intentionally let her husband bleed to death (almost certainly a fabrication).

She later remarried another load of a man: cranky crackpot and former vice president Aaron Burr, back in the Us after his previous transgressions were forgiven. He was as good a businessman as Stephen Jumel and had soon ruined the family yet again. Fed up with the looser, Eliza procured a divorce , her end of the legal arrangements handled by none other than Alexander Hamilton, Jr. Burr died later that day.

Eliza lived out the rest of her days in the mansion as a recluse until she passed away in 1865 at the age of 90 and was buried in nearby Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum. But some say her spirit didn’t make the move across town and remains still in the old mansion. She reportedly materializes from time to time to scare groups of children touring the mansion, but more often she is reported to inhabit the antique clock on the mansion’s first floor. Those working at and touring the mansion have claimed to hear a thin, ethereal voice telling them to leave or be harmed. Other ghosts—including a young servant girl who committed suicide by jumping out a window and a soldier from the American Revolution—keep Mrs. Jumel company.

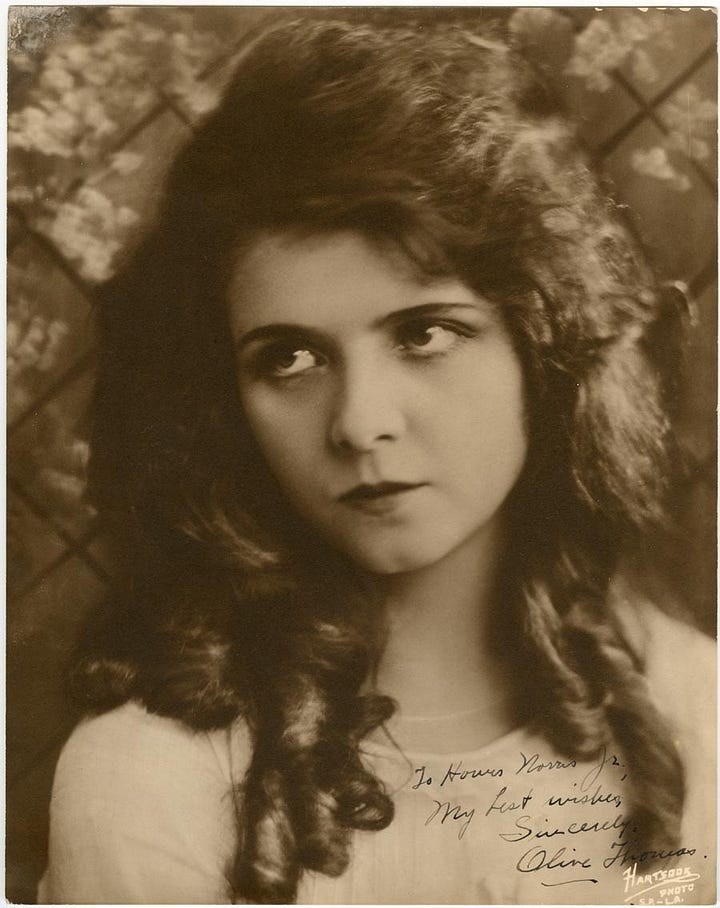

New Amsterdam Theater – Otherworldly Olive

The tragic tale of showgirl-turned-actress Olive Thomas begins in 1915, when her career as an “illustration model” got her a part in the famous Ziegfeld Follies show at the New Amsterdam Theater. She was a star attraction of the lavish revue, and in 1916 parlayed that fame into a successful screen career. That same year, she married Jack Pickford, brother of silent film superstar Mary Pickford. The two had a famously tumultuous relationship, with multiple break-ups, public spats, and salacious scandals. Jack was an unrepentant womanizer, and for his philandering he was awarded with a case of syphilis. At the time, it was common to treat the affliction with mercury bichloride — mercury salts. After the two had been out on a wild all-night bender in Paris, Jack passed out in a drunken haze. Olive, unable to sleep, went to the medicine cabinet to take some sleeping tonic. Jack was stirred from his whiskey-induced reverie by the sound of his wife screaming. In her own hazy state of mind, she had mistaken his mercury bichloride for her sleeping medicine. After several agonizing hours in the hospital, her body going entirely septic, Olive Thomas passed away.

Her death was investigated and ruled a tragic accident—at least in court. In the press, things were different, and the whole sordid affair is generally considered to be the first major publicized scandal. Some said Olive committed suicide because of Jack’s infidelities, or because she discovered she had contracted syphilis from him. Others said the dastardly Jack had intentionally poisoned his wife. Still others claimed Olive was a drug addict who indulged in “champagne and cocaine orgies.” In all likelihood, the conclusion of the police was the correct conclusion: it was a terrible accident. Olive was buried in New York’s Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. But some say her spirit returned to the New Amsterdam Theater.

From the front of the modern New Amsterdam, it’s hard to imagine what it was like in the 1910s. The building became the lynchpin of the revitalization (or Disneyfication) of Times Square in the 1990s, and it is now home to assorted Disney productions. But in Olive’s time it was home to the Ziegfeld Follies, the opulent brainchild of showman Florenz Ziegfeld. It was a combination of lavish song and dance shows, outrageous costumes and sets, and (especially on the rooftop garden) scandalously skimpy attire for the female performers. While little remains to remind one of the theater’s past, back stage and upstairs is a different matter. Olive’s ghost is said to appear backstage—has been doing so, apparently since as early as right after her death. During the renovation of the theater by Disney, the night watchman apparently contacted the new manager in the middle of the night, wanting to resign after having seen a beautiful, ephemeral woman wearing green beaded dress and holding a blue bottle (the bottle of medicine that killed Olive) on stage. When he went to confront the trespasser, she glided off stage and disappeared through the wall.

Since it reopened in 1997, the New Amsterdam has seen Olive reappear many times, often to young male actors with whom she will flirt and toss a playful, “Hi, fella!” their way. Her ghost has been seen floating across what would have once been the glass-floored roof garden (which in its day served intentionally as a peepers’ paradise) and lurking upstairs in the offices. Although normally a playful and harmless ghost, she does tend to throw a tantrum—shaking sets and making a racket—whenever a set for a new play is being built, or whenever her former Follies co-stars visit. A picture of Olive remains backstage, and performers greet her regularly for good luck.

I keep meaning to get my hands on Spindrift: Spray from a Psychic Sea by Jan Bartell, that details her time living in the House of Death. Have you read it?